In This Article

What Zoning Regulates

Permitted Uses And Special Exceptions

Special Zoning Districts

Cluster Zoning

Zoning Variances

Nonconforming Lots And Uses

Planning to Subdivide?

Waterfront Property

Beyond Zoning: Should You Build Here?

Read & Post Comments

See also LAND USE REGULATIONS View all LAND BUYING articles

Local governments establish zoning ordinances in order to regulate land use in accordance with goals set by the local planning board. The goal of land use planning is to promote a livable, and economically viable community, balancing the needs of homeowners, businesses, agriculture, recreation, and other community priorities. A title search can establish who owns a property, but will not tell you anything about its zoning status.

Local governments establish zoning ordinances in order to regulate land use in accordance with goals set by the local planning board. The goal of land use planning is to promote a livable, and economically viable community, balancing the needs of homeowners, businesses, agriculture, recreation, and other community priorities. A title search can establish who owns a property, but will not tell you anything about its zoning status.

WHAT ZONING REGULATES

Zoning regulations generally divide the land into zoning districts, such as Residential, Commercial, and Industrial, and further into sub-districts such as R1 and R2, each with different rules. For example one residential district may only allow only single-family detached homes, while another may allow duplexes and certain in-home businesses. In general, single-family residential districts are the most heavily regulated.

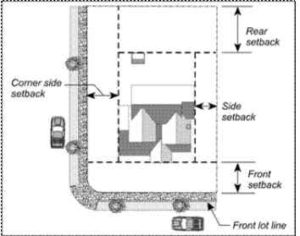

Zoning regulations typically govern the density and type of housing, including such things as minimum lot size, the minimum distance from the property lines (setbacks), building height, and what percentage of a lot may be built on or paved (lot coverage).

Setbacks are often different for front, side, and rear yards, and for different types of structures. These can range from as little as 2 feet to 40 feet or more, so these can leave you with little choice as to where to place your house on the site.

Zoning rules may also regulate such things as parking requirements, in-home businesses, and even the legality of “in-law” or “granny” apartments, whether you can keep chickens on the property, or start a home business. The number of bedrooms may also be limited by zoning as well as by the health department in rural areas with septic systems.

The purpose of zoning is to control density, noise, and congestion in a neighborhood. No one wants a high-rise or pig farm built next door to their new home. Safety is also a concern. For example, setbacks keep houses separated to prevent fire jumping from one house to the next.

Violating zoning rules is always a bad idea, even if you have a seemingly valid building permit. If you build too close to the lot line, violate height restrictions, or build on a wetlands, you can be forced to modify or, in extreme cases, dismantle some or all of the construction.

At a minimum, you can face big legal bills and enormous headaches. I frequently drive by a house with three feet chopped off the top of the roof (see photo) due to a violation of the height restriction in the zoning ordinance.

PERMITTED USES AND SPECIAL EXCEPTIONS

It is important to understand the zoning rules that apply to your building site. A good place to start is to pick up a copy of the zoning map and ordinances at the local town hall. Zoning ordinances typically include permitted uses and special exceptions. Permitted uses are those that are allowed without any special permission. Special exceptions need to be applied for, and are generally granted if the applicant has complied with the established standards.

Special exceptions typically require a special review by the town, and are decided on a case-by-case basis. The town may grant the exception, require additional design changes, or deny the exception. You can appeal, but need to decide whether this is worth the time and money.

An example of a special exception for land near the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland reads as follows:

All property in Anne Arundel County within 1,000 feet of tidal waters is located in an area known as the Chesapeake Bay Critical Area. An applicant applying for a special exception within this area must submit a Critical Area report with the special exception application. This report contains written findings addressing the impact of the proposed construction on the property and the measures that will be taken to lessen or eliminate these impacts. It is important to note that the Office and Planning and Zoning will not accept an application for a special exception in the Critical Area without a complete Critical Area Report.

SPECIAL ZONING DISTRICTS

Special districts often have stricter zoning rules than standard districts, sometimes prohibiting all building. These often overlay the standard zoning district map, creating rules on top of rules. Examples include historic districts, coastal or waterfront lots, aquifer districts, environmentally sensitive areas, steep slopes (hillside conservation districts), ridge lines, forested areas, wetlands, and flood plains.

Environmentally sensitive areas, such as coastal and other waterfront areas, often have major restrictions, making building there very costly. Areas defined as wetlands are also highly regulated and what is considered a wetland is not always obvious. Land that is classified as wetlands may not appear wet or marshy or even contain marsh plants such as cattails. Even if building is allowed in a special district, you may need to use special, costly septic systems, erosion control measures, and other environmental safeguards.

Historic districts may restrict the size, shape, design, color, and exterior finish of your house. Don’t make any assumptions. Check out any assumptions or representations by the seller with the local building and planning jurisdiction.

Other restrictions that you might not think of may include:

- Views: Some areas require that buildings not be visible on ridgelines, near a lake shore, or other scenic areas.

- Trees: Some areas restrict the size, number, or area of trees that can be cut – even though you own the land.

- Restrictions due to archeological sites, threatened species, aquifer protection, and on and on

CLUSTER ZONING

A number of semi-rural and rural areas now encourage cluster zoning, where a developer is allowed to make house lots smaller and closer together in exchange for designating a percentage of the parcel as conservation land. This helps maintain larger tracts of open land, which is better for preserving natural ecosystems and wildlife, as well as for outdoor recreation. It’s a tradeoff – you’re closer to your neighbors, but border on a large parcel of conserved land.

ZONING VARIANCES

If your plan does not to strictly comply with the zoning rules, but is not considered detrimental to the public or to neighboring properties, you may be granted a variance, allowing you to deviate from the zoning rules. The most common type of variance is a “hardship” or “use” variance. These are governed by town law and, in general, are granted when the shape or size of the lot interferes with the owner’s “reasonable use” of the land, and the problem has not been created by the landowner.

For example, the town may let you build on a lot that is too skinny to comply with the setback rules. Variances are granted all the time, but may also be denied, based on how local authorities interpret such concepts and “hardship” and “reasonable use.” In some cases, the town will let you proceed with a “special permit,” which is simpler to obtain than an variance.

Abutters are generally notified of variance requests and approvals and have the opportunity to raise objections with the zoning board. Buying a lot with the hopes of winning a variance is a risky proposition. Best to talk to town authorities and a local real-estate lawyer with experience in the local area. Although it is unlikely, your variance may still be challenged by abutters after being granted by the town (see Lessons Learned).

The safest approach is to make the lot’s purchase contingent on approval of the zoning and building department for your intended project. If your right to proceed with your building plans cannot be established, it’s probably best to walk away.

NONCONFORMING LOTS AND USES

A nonconforming lot is one that does not comply with current zoning rules, but may have been buildable under the zoning laws at the time the lot was first deeded or subdivided. The rules governing nonconforming lots can be complex and may turn on who owned the land at specific dates. The town’s zoning office can be very helpful in untangling these issues, but make sure you get their opinion in writing, before committing to purchasing the lot. A lawyer’s opinion may be a good idea if there is any uncertainty.

A nonconforming use applies to an existing building that is not in compliance with the current zoning rules. This is primarily an issue for people who want to add living space – or tear down and rebuild from scratch. The rules vary from town to town, but most follow the principle that you cannot make a non-conforming building more non-conforming when you remodel or rebuild. In some cities and towns, you can apply for a “special permit” to add to a non-conforming use. In general, a special permit is easier to obtain than a variance.

For example, if a building violates the current setback requirement, you cannot enlarge a porch or deck, or build an addition, that is even closer to the property line – making it more non-conforming. Even if the building’s footprint remains the same, adding space upward might be rejected as a “volumetric” change. If the building is torn down or destroyed by fire, you may or may not be able to rebuild on the same non-conforming footprint, depending on how the local law is written and interpreted.

This has become a contentious issue in many vacation communities, where someone buys a non-conforming shack by the sea and then tries to “remodel” it into a McMansion several times larger than the original structure (see photo). Even if you manage to win the town’s approval, you may still end up with some very hostile neighbors.

PLANNING TO SUBDIVIDE?

If you’re hoping to subdivide the lot you are purchasing in order to sell off a parcel, you’ll need to look into the town’s subdivision regulations. These may be part of a municipality’s zoning ordinance or may be a separate set of regulations, creating restrictions above and beyond the zoning rules. Subdivision regulations can be complex and may need a lawyer’s review.

ON THE WATERFRONT

Waterfront properties entail higher costs and greater risks than most. Special zoning rules, stringent on-site sewage regulations, and other restrictions significantly drive up building costs. In addition you are taking on the risk of greater storms, rising sea levels, and increased coastal erosion. Environmental scientists are predicting that the 100-year flood will soon be the 80-year flood, then the 60-year flood, and so on.

If you are undaunted and determined to live on the water, there are steps you can take to safeguard a home – for example building on reinforced concrete piers with break-away walls on the first floor, designed to wash away in a flood but preserve the rest of the house (as is commonly done in flood-prone areas such as the Florida Keys). Also plan to budget for exorbitantly expensive flood insurance, if available, in such areas.

BEYOND ZONING: SHOULD YOU BUILD HERE?

Finally, just because the governing jurisdiction allows a building to go up, it doesn’t mean it’s a good idea. Steep hillsides may be vulnerable to erosion or landslides depending on the soil types, drainage patterns, and other factors. Low-lying areas near a pond, lake, stream, or saltwater may be flood-prone, whether or not the state calls it a wetlands. What looks like a piddling little stream in the summer or fall can turn into a raging torrent next spring. Consulting with a geotechnical and/or environmental engineer might be wise in this case.

See also LAND USE REGULATIONS

View all LAND BUYING articles Back to Top

Toni Mac says

Do I Have Grandfathered Right To Rebuild Cottage?

I have a lot that had two cottages on it. The tenants during Covid destroyed my home. The town made me tear it down stating that it was unsafe. Have I lost my grandfathered rights to rebuild my home.

buildingadvisor says

Grandfathered property rights generally exempt a landowner from regulations, such as zoning ordinances, that were enacted after a home was built. For example, a home may be too close the property line under current zoning, but the setback was allowable when the home was built. The house is considered “non-conforming” under current zoning rules, but permitted under a grandfathering clause in town regulations.

Exactly which rights are grandfathered and under what circumstances will vary from town to town, so you need to check with your local building or zoning department. Also, some grandfathering rules can lapse if the homeowner waits too long before taking advantage of the right.. Other grandfathered rights, such as the use of a non-conforming septic system, may terminate when a property changes ownership.

In many areas, you are allowed to remodel or rebuild a nonconforming structure is you remain within the footprint and height of the original building. To change either the footprint or height often requires a variance or special permit. There is a good chance that the town will let you rebuild if you stay within those parameters.

The sooner you contact the town about your desire to rebuild, the better. If they accept your proposal, submit plans and get your building permit as soon as possible. If you wait, the next zoning official may rule otherwise. You can always renew or revise the permit as needed. Get any opinion in writing, if at all possible. If you are not successful with the town, , a real estate lawyer may help you find a workaround that is acceptable to the town – possibly through an appeals process.

JW says

Is Non-Complying Lot Buildable?

Hi I am thinking of buying a parcel of land in Mercer County NJ.

From the zoning officer, “the lot is non-complying and a variance would be required for lot width and frontage. There appears to be substantial wetlands and riparian zones that would need to be identified in order to determine if and where a new house could be built on the vacant land”.

I would like to seek a professional opinion on whether the lot is buildable.

buildingadvisor says

I would advise you to proceed cautiously with this piece of land. I doubt if anyone can tell you, with complete confidence, that you can obtain the variance(s) or special permits (variance lite), required to build on a non-complying or non-conforming site.

These decisions are typically voted on by the Zoning Board of Appeals (or similar board), whose members have a lot of discretion as to whether to approve your project. It’s difficult to say in advance whether a specific project will be approved or what conditions or changes the board may require for approval.

Also, abutters will be notified and can have input which can affect the board’s decision.

The safest bet – if the seller will accept this – is to make your offer contingent on your getting the necessary approvals to build your project. This could tie up the sale for a few months or more, so it may not be acceptable to the seller.

But otherwise, you are assuming significant risk the lot will not be suitable for the type of construction you have in mind — or it may not be buildable at all.

Yavuz Bingol says

What Can I Build In a Wellhead Protection Area?

I have 5 acres land and it’s at the Wellhead Protection Areas B and C1, could I build a house there or make a subdivision plan ?

buildingadvisor says

A federal law, the Safe Drinking Water Act, requires states to protect public wells from surface contamination by establishing Wellhead Protection Areas. The regulations apply to wells used to supply portions of the community with drinking water.

Each state has its own zoning and subdivision regulations for these protected areas, so you need to check with your individual state. Areas closer to the well have greater restrictions. Contact your state’s Department of Health or Department of Environmental Protection for details.

The goal of these laws is to keep toxic chemicals and other pollutants out the wells that serve the public. In general, commercial and industrial uses are strictly limited in Wellhead Protection Areas, while single-family home are more lightly regulated. Subdivisions may be allowed but with some restrictions around density, stormwater management, and septic systems. In most cases, any construction or commercial usage in these areas requires special permitting.

The bottom line is this: Don’t assume anything about what you can and can’t build in a protected area. Arrange for a meeting with the zoning department to discuss your plans. Get any opinions in writing. In many communities, getting anything permitted can be difficult and time-consuming. In a protected area, the hurdles will be greater.

Renee says

Can We Tear Down Grandfathered Home to Build New One?

Currently looking at a New England property with just over 2 acres. On the property there’s an old mobile home that’s been “converted” (from what I gather it looks like it was affixed to a permanent foundation, maybe drywalled, and vinyl sided). The zoning laws prohibit mobile homes, but this one happens to be grandfathered. The zoning laws also states that the property must have a minimum of 200ft of frontage to be an acceptable building lot. This lot has only 100 ft.

Our real estate agent believes that if anything happened to the current building the lot would be unusable. Similarly, we would not be able to tear it down and build a stick-frame or similar style house in the future. As I am planning to go to grad school for architecture, designing and building our own home in the future was definitely the hope with this piece of land. The parcel is zoned as residential, has septic and a well. Any advice on how to proceed would be so appreciated. Thank you!

buildingadvisor says

Grandfathering rules are often complex and subject to interpretation by the zoning administrator. It’s risky to assume that the grandfathering rules will accommodate your intended plans. You really need to confirm this ahead of time with the zoning department.

Grandfathering rules are often based on the date of the original construction and the zoning rules in place at that time. As your real estate agent pointed out, the grandfathered status that applied to the mobile home may not apply to a remodeling job that changes either the footprint or height of the building. It’s even more unlikely that they would apply to a completely new building.

If you wish to keep the existing structure and either increase the footprint or the height, you will probably need a special permit or possibly a variance, which is more difficult to obtain. The principle at play is this: If the work you are planning makes a non-conforming building (one that does not comply with current zoning) more non-conforming, then you will need to obtain a special permit or variance. For example, if you wish to enlarge part of a building that violates the setback rules, this would make it more non-conforming and require special permission.

There is never a guaranty that a special permit or variance will be granted. Also you may need to test the well and update the septic system, starting with a new perc test. Any of these things could be a deal breaker and make the lot effectively unbuildable.

Bottom line: You have a lot of homework to do before you can have any confidence that this lot will meet your current and future needs. Do not assume anything. In you make an offer, make sure you have contingencies in place that allow you to research the lot’s zoning status as well as the condition and status of the well and septic system. Schedule time with the local zoning office and discuss what you wish to do. If you feel like you’re over your head, hire a real estate lawyer to help you write an offer and conduct the necessary research

John says

Buying Land With Variance Required

Good morning,

I have been looking at a piece of land near me and exactly where I want to build here in coastal southern Maine. The only catch is – the land is not YET buildable due to an ordinance regarding road width. We are 1.5 feet too narrow for it to be deemed buildable. We are still renting and are in no rush to get our issues pushed through the zoning board. It is a 5.7 acre lot, which could be later subdivided. The price is way under the value following board approval and we could easily sell a parcel later that would position us very nicely financially. Please advise.

buildingadvisor says

There may be a reason why the price seems so low. Buying land with the expectation of a zoning variance is very risky. There is never a guarantee that a variance (or even a special permit) will be granted. The same is true for approval to subdivide. I don’t know your local area, but in general, many towns have an anti-development bias and don’t make it easy to subdivide or build.

Also make sure the land has passed a perc test if you will need a septic system on site.

I’d strongly suggest meeting with the town’s zoning officials, with the relevant site plans and other information in hand, and explain what you are hoping to do. With any luck, you’ll leave with a better idea of the obstacles ahead and your chances of success.

u could also make obtaining a variance a contingency of the offer. However, it’s doubtful that the owner would accept the offer because of the time required. This variance process can take several months or longer.

At some point, you may need to hire a lawyer with zoning experience in your area to make a formal request for any variances or other approvals you will need.

Also consider the cost of site development, which is often a lot higher than people imagine. It can sometimes be as high as the cost of the land.

Tom says

How to Build Two Houses on an R1 Lot?

Hello. We recently purchased a home in Monterey Park, CA with a very large lot (for the area) of 24,000 square feet The lot is roughly 60 x 300. The only access is the 60 foot end of the property bordering the street. Zoning is R1. The house is near the front of the property and is 1,400 square feet.

We would like to be able to build a second full size house on the back of the property in some way. To my knowledge the only possibilities to accomplish our goal is 1) get an easement and subdivide into two lots, or 2) get some kind of variance/exception so that two houses are allowed on this R1 property.

For what it’s worth, according the records, the lot used to be two separate lots with the rear lot not having any road access. Can you think of any plan which will have a chance of success?

buildingadvisor says

Zoning is an intensely local phenomenon, so it is difficult to generalize. There are as many different zoning laws as there are cities and towns in the US.

I’ve seen projects built that were clearly in violation of the law and projects blocked because of some obscure legal technicality. And it can get very technical when you get into the weeds of interpreting the often lengthy and convoluted regulations. What, exactly, is a home-based business or accessory use? Who determines if a project is “detrimental or offensive or tends to reduce property values…by reason of dirt, dust, glare, odor, fumes, gas, sewage, refuse, noise, or traffic congestion”?

In your case, you may be dealing with both zoning and subdivision regulations adding another level of complexity. Both can be affected by grandfathering rights that often depend on the timing of the original subdivision or, in your case, the combining of two lots into one.

The first thing to do is to familiarize yourself with the local regulations, which are usually posted online.

In some cases, a second house is allowed in an R-1 zone if the total square footage and number of bedrooms is permissible under current regulations. However, you may run into problems if both units contain a kitchen, often the factor that defines a dwelling unit.

The fact that your land was formerly two separate lots may help you get a permit it to subdivide, so that is worth exploring. As you mentioned, an easement would be required for access, but you would be granting yourself the easement — usually not a problem. But minimum road frontage could still be an issue.

If subdividing is not an option, you might be able to designate one of the buildings as an accessory dwelling for relatives or a disabled person, as allowed in some jurisdictions. Some make exceptions for affordable housing units.

Most likely, you will need a special permit (relatively easy) or a variance (more difficult) to move ahead. Both of these require a formal application, notification of abutters and neighbors, and a hearing, where neighbors can voice their support or objections. You can appeal an unfavorable finding, but approval is never guaranteed.

Politics plays a big role. Some jurisdictions support the creation of additional housing units and will try to work with you and some fight it tooth and nail. It never hurts to hire a lawyer with extensive experience with the zoning board in your area. A lawyer can help you assess the likelihood of success and strategies to get there.

It also doesn’t hurt to meet, in person, with local zoning officials to describe your goals and get their input. Come armed with pertinent facts, preliminary drawings, and knowledge of local regulations. With any luck, you’ll come away with a rough idea of the road ahead, options worth pursuing, and your chances of success.

Tom says

Where to Find Lawyer for Variance Application?

Thanks for your advice and knowledge. From what you say and what I’ve gathered from speaking to our City’s building and zoning departments, our best hope to get permission to build a second house on our property appears to be to consult a lawyer with expertise on these matters that has experience in our local area. Do you know where we might look or who we might ask to find someone like this? Thanks.

buildingadvisor says

Finding a lawyer is not much different than finding a dentist, architect, or any other professional. Do a little networking.

Start with the lawyer who handled your closing or other lawyers you have worked with and ask them who they would recommend for a variance application in your jurisdiction.

You can also get names from real estate agents, loan officers at your bank, or anyone you know who works in the real estate industry.

Another place to start is your state or local bar association, most of which have lawyer referral services — or if all else fails, type “zoning lawyer” or “lawyer zoning variance” into Google.

Once you have a few promising leads, call and screen them over the phone. They may charge a nominal fee a brief initial meeting to feel them out on fees, strategies, and the likelihood of success. By all means, ask how often they have applied zoning variances in your town and ask for an estimate of costs and a timeline to apply for a variance. Including the prep work, plan on at least a few months – or longer if multiple meetings and revisions are needed.

Kim says

Should Closing Lawyer Have Found Zoning Violation?

I bought a house 4 years ago. After having a survey done, it was brought to our attention that the lot is not “nonconforming” it is noncompliant. This is a huge problem for us because they are no longer granting variances.

Shouldn’t our closing attorney have found this out prior to us purchasing the house?

buildingadvisor says

Zoning laws are often quite complex and can vary a great deal from one jurisdiction to the next. Almost all zoning districts have rules regarding non-conforming properties. These are typically properties whose usage (say, two-family) or physical characteristics do not comply with the current zoning law.

Some areas refer to any building that is physically nonconforming as non-complying or non-compliant. The building might be too high, too large, or too close to the property line. These are generally treated the same as buildings with nonconforming uses.

In most cases, the nonconforming property was built before the zoning law was enacted or the zoning rules changed after the building was completed. In most cases, if the issue was pre-existing current zoning, it is considered a legal nonconforming use. These are typically “grandfathered” under current zoning, but with restrictions on how the property can be modified or used in the future.

In general, you cannot do anything that makes a nonconforming property become more nonconforming. For example, you can’t add on to a portion of the house that violates setbacks. You can’t turn your non-conforming 2-family into a 3-family. Also, buildings can lose their legal nonconforming status if they are abandoned for a certain period of time or badly damaged.

It gets tricky if your property is challenged by an abutter or by the town (for example, when you apply for a permit) and you cannot prove that the building or its use qualifies for legal pre-existing status. In that case, you may need to apply for a variance or the town can require you to change the use or physical characteristics of the building.

It’s uncommon, but towns have required people to lower their roof or remove an illegal second story to comply with zoning. In what way is your house considered non-compliant?

Should your lawyer have discovered this and informed you prior to buying the home? It would have been nice, but I think you would have a hard time proving that the lawyer was negligent. Unless asked to do a more thorough investigation of building’s zoning status or other issues, the main job of the buyer’s lawyer is to establish that clear title is transferred to the new owner for the agreed-to price and terms.

It is part of the buyer’s due diligence to look for problems with compliance with zoning and building codes, in addition to the building’s condition. As you discovered, this falls in the domain of a surveyor, not the closing attorney.

I don’t know the particulars, but many towns will consider granting a “hardship” variance for situations where compliance with zoning would place an unfair burden on the homeowner. A good real estate lawyer who knows the ropes in your local area might be able to help – not that you’re eager to hire another lawyer.

Best of luck!

Kim says

Thank you Steve. Our house is located in Cape Cod. The house was built in 1972 on a lot created by dividing the adjacent lot. At that time they did not seek a variance to create a new “non-conforming” lot. In which case, we now have a non-complying lot.

We live in a district of critical planning, which does not issue new variances. We need to do structural work to our home and we wanted to add a second story. Which neighbors have done with a special permit.

The language in the DCPC (Districts of Critical Planning Concern) states it has to be a “legal” lot, which we currently don’t have. What a mess!!!

buildingadvisor says

I agree – sounds like a mess.

I’m familiar with DCPCs (as I also own a property on Cape Cod), but have never had to deal with one personally. There are only 12 on the entire Cape. The DCPC designation allows a town to impose moratoria or other extreme restrictions on development in these areas, beyond the reach of normal zoning laws.

It certainly looks like it would be rough sledding to get a variance or special permit to do the work you have in mind. A local lawyer well versed in local zoning appeals would be your best bet. They could help you evaluate whether it’s worth the time and expense of filing the necessary requests and appeals.

FYI: I built a house on Cape Cod in the 1990s – a nonconforming house on a nonconforming lot. Because the lot was legally subdivided prior to modern zoning laws, I was able to build a three-bedroom house with minimal setbacks on a small lot. The project, including two variances, sailed through zoning and permitting without a hiccup. I was the GC at the time.

Fast-forward twenty years and we decided to add a bathroom above an existing porch, without changing the house footprint. It took the better part of a year to get a special permit – after jumping through numerous hoops and submitting 13 copies of a 30-page appeal to the local ZBA and attending a special-permit hearing. Needless to say, it’s not easy to build anything on Cape Cod in the modern era.

On the other hand, we’ve all seen projects get built that never should have and special treatment of individual projects for a variety of reasons – sometimes simply the wealth of an individual who has “lawyered up” and outguns the local planning board. Or exceptions may be made for locals, special hardships, or people with connections. In my experience, enforcement of zoning laws is very inconsistent as zoning boards have a lot of discretion in how they treat appeals. The ZBA members are volunteers who do their best, but are often over their heads in a very complex area of law.

That said, there may still be hope that you can move ahead with your project, maybe with some modifications, but it won’t be smooth sailing.

Amir Nasiri says

Neighbors Are Encroaching on Land I Purchased

I purchased a building lot long-distance. I have since discovered that I cannot access the land without crossing the property of others. I have no frontage on a public road. I have also discovered that some of the abutters have built driveways that cross my land, and another has used a portion of our land to expand their own land. Finally, the town is telling me that the land is “not buildable.” Any suggestions would be appreciated.

buildingadvisor says

This sounds very frustrating. It’s important to do your homework and learn as much as possible about a piece of land before purchasing and to add appropriate contingencies to your offer. It’s too late for that, but hopefully, you will be able to work through the current challenges and develop the land as you had planned.

When you buy land, you are given a deed and other legal documentation designating the boundaries, as well as any easements, rights-of-way, or other restrictions on your use of the land.

It’s possible that your neighbors have the legal right to cross your land along a right of way or easement. It’s also possible that they have been doing so for many years without permission.

If they have been using the land this way for many years, without any opposition from the owner, it’s possible that they could claim ownership of the land, or at least a right-0f-way under the ancient principle of “adverse possession”. This type of claim must be established by a court and state laws vary a lot on the specifics. But it is something to be aware of as you go forward.

On the other hand, it’s quite possible that your neighbors are just using the land as a convenience because no one has told them not to. They may not even know the location of the property line. In either case, they are trespassing and need to told to cease encroaching on your land. You can try the friendly route by talking to them, but if that doesn’t work, you will need to notify them in writing. If they fail to comply, you may need to hire a lawyer to write a more persuasive letter and possibly to take legal action to protect your property rights.

Whether or not the lot is buildable is a separate issue. I’m not sure who told you it was unbuildable or what is the basis of that claim. Zoning laws can be very complex. Some lots are considered unbuildable because they are too small, lacking sufficient road frontage, or are in a wetland or other environmentally restricted area. Or they may fail other regulatory hurdles such as passing a perc test.

You will need to dig deeper to understand the specific reason cited, and explore possible work-arounds. I’ve seen more than a few “unbuildable” lots that got built on. Sometimes lots are unbuildable under current zoning laws, but are “grandfathered” under the zoning laws in place when the lot was subdivided. If access is an issue, may be able to obtain a right-of-way to a public road. If the issue is a failed perc test, you may still qualify for an alternative septic system. In some cases, a zoning variance or special permit will be required to move ahead.

Once you’ve done your research, sit down with the building and zoning department, explain what you are trying to do, and ask for their advice. In most cases, these folks will appreciate being consulted and want to help you succeed. If you do need a zoning variance or other regulatory exemption, then hiring a local real estate lawyer could be a good investment.

Steve says

Can I Use My Own Builder on Developer’s Lot?

I was introduced to a couple of RTI / Shovel Ready properties by a broker. Does it mean if I purchase an RTI (ready-to-issue-permits) development site, I will have to use their approved architectural design because that’s what the ready-to-issue permits are based on? I’m really confused and hope I can get this sorted out. Thank you for your time Steven!

buildingadvisor says

If you are buying a lot from a developer with a house-and-land package, you may be contractually required to use the developer to build the house. You may also be required to use their designer. In other cases, you have the right to purchase the land outright and find your own builder and designer. But design approval by the developer may still be required. Simply ask the developer if you can select your own builder and whether design approval is required. Get the answer in writing before committing to the lot purchase.

Design approval can be based on written standards concerning, style, size, siding, color, etc., or may be completely at the discretion of the developer or a design-review board.

RTI (ready to issue) is a term used in Los Angeles to indicate that a project has passed through all steps of the area’s complex permitting process, and the city is ready to issue permits once an application is filed by the owner or contractor. If you change the architectural plan, then you may need to resubmit the new plans to the permitting process. In changes are minor, you may be able to expedite the process by updating existing permits and approvals. Some of the permitting, such as septic, well, curb cuts, etc., may carry over to your new plans, but you cannot make any assumptions.

In general, permitting is easier in a developed subdivision than on raw land, but if your plan differs significantly from the approved plan, then you may need to start from scratch with at least some of the permitting. For example, if you change the footprint, location on the lot, or number of bedrooms, you may need a new or updated permits for zoning, building, and septic design.

Get clarification, in writing, from the developer before proceeding. Also, it never hurts to meet with the local zoning and building departments to review your plans and identify any red flags. Since permitting and plan approval in your area is so complex and time-consuming sticking with the original plan, with only minor revisions, might be the easiest way to proceed.

Misty Gann says

Can I Build a Small Multifamily On This Lot?

I am looking at buying a lot to put a quadplex on. The property perks, but how do I know if it will accommodate this size structure. (It will be a total of 8 bedrooms, 8 baths, and 4 half-baths)?

buildingadvisor says

Before the building department will issue a building permit for your project, you will need approvals from the health department (perc test) and the zoning department.

The land passed the perc test, which is a good start. Next you need to make sure that the lot has adequate room for the leach field required and, often, for a replacement field as well. The size of the leach field is determined by the perc test results along with the total number of units and bedrooms.

The leach field must meet adequate setbacks and clearances to buildings, property lines, wells and water lines, and other property features such as open water or drainage ditches.

Before wasting money on a preliminary septic design, I would focus on zoning, which you can usually investigate for free. Start by downloading the local zoning regulations from the town, city, or county’s zoning department. Every jurisdiction in the U.S. has its own zoning regulations, so you really need to check with the local zoning department to see if your project will fly.

Most jurisdictions include one or more residential, business/commercial, and industrial zoning districts – designated usually as R1, R2, R3, C1, C2, and so on. Some also have special RM districts for residential multifamily and may have other districts for mixed-use and other types of development. Each district permits certain uses and prohibits others.

If the units are to be rented, the project may be considered a commercial property and may need to be in a commercial zoning district.

In addition to your project being a permitted use, it must also comply with other zoning rules regarding size and height of the building, lot coverage (percent of the lot used for structures and paved areas), setbacks from the property lines, parking requirements, and anything else they choose to regulate.

I recommend scheduling a meeting with a local zoning officer and bringing in your preliminary plans. Ask whether your plan will be acceptable without any variances, special permits, or other hurdles that can tie things up, cost time and money, or kill a project altogether. You may find that with minor modifications, your project will be able to comply.

Better to find out now than after you make the purchase. Also, zoning and building officials appreciated being consulted beforehand – it can make things go a lot smoother once the project is under way.

Read more on Zoning.

Toni Raines says

Zoning for Duplex

What kind of zoning do I need to build a duplex?

buildingadvisor says

Typically R1 zoning allows for one single-family house on a lot, while R2 allows for a two-family or duplex. R3 allows for larger multifamily dwellings and condominiums. In zoning regulations, R typically stands for residential and C for commercial. Zoning also regulates what activities and business types are allowed on the property, and physical constraints such as building size, height, and setbacks.

In some cases, there are loopholes that allow for more than one dwelling unit in an R1 zone, such as secondary in-law apartments or space for an elderly or handicapped person – a so-called “granny flat.”

Everything about zoning varies from one jurisdiction (city, town, or county) to the next. Nowadays, you can usually find zoning maps and regulations online and read specifically what is allowed and prohibited. However, like all laws, these are subject to interpretation so if what you are planning lies in a gray area, it is best to get approval from the zoning administrator before proceeding.

If you violate a zoning law and the town decides to take enforcement action, they can issue stiff fines or even make you alter or remove the structure that is in violation

Randy Ray Young says

Not Enough Frontage To Subdivide

PLEASE HELP. State of Maine. Parents passed away and they were living with my brother. I have 5 other siblings. We want to sell the land to sisters boyfriend and let brother keep house and garage. Boyfriend will build up in the back on the 36 acres. The town of Litchfield now says we can’t break up the property as there is a 200 foot frontage code. The buyer (sisters boyfriend) can only buy all of the property and would have to tear down house and garage. Brother gets kicked out on the streets. There must be a way around this. It IS our land isn’t it?

buildingadvisor says

Going against a town on a zoning issue is tough. I just spent 18 months getting a permit to add a 10×10-foot bathroom to a house we own due to a zoning issue.

Subdivision regulations are usually separate from zoning ordinances, but are generally handled by the same town office, typically called the zoning board or zoning commission. These rules are enacted at the local level, consistent with state law. Each town makes its own rules.

People sometimes ignore zoning regulations and build what they want, but they risk having the town respond legally at a future date – in some cases, forcing the person to modify or remove the construction that violated the regulations. It can get pretty messy.

A better bet is to apply for a variance, which lets you bend the rules a bit. There is something called a “hardship” variance which could apply in your case. It is possible that the town would allow you to, for example, build a private road that would provide the necessary frontage for the second lot.

Some towns also have zoning provisions that allow additional dwellings to be built on a lot under special circumstances. For example, if the living space is for an elderly relative, handicapped person, or for low-income housing, some towns will allow an “affordable and accessible” dwelling to be built. This does not require a variance, but would still require a special application.

Applying for a variance can be complicated, the process slow, and there is no guarantee of success. Many people get help from a lawyer in filing an application for a variance. Even if you want to go it alone, a brief conversation with a good real estate lawyer in town might be worthwhile. The lawyer could tell you your chance of success and outline the steps required to properly file.

If you haven’t already, you should also schedule a meeting with the town’s zoning officer, explain what you are trying to accomplish, and ask about possible ways to meet your family’s needs. If you are lucky, you will someone in the zoning department who is sympathetic to your situation and who can guide you through the process.

Robert Nearhoof says

Building in Critical Areas

I would like to subdivide my current property to build on the section that I subdivide. I live in the critical area and I have used roughly 3,900 square feet of impervious surface on a lot that has 33,750 square feet. I would like to know what percentage of property can be used in the critical area and if I subdivide my property, roughly 100 feet by 125 feet, can I build on that portion . Thanks, R.N.

buildingadvisor says

Your questions are all governed by zoning rules, which are enacted and enforced at the local level, sometimes with overriding state laws for issues such as development of “critical areas”. Critical areas are generally designated by the state as environmentally sensitive and may include such things as wetlands, tidal areas, buffers around lakes and streams, wildlife habitat, and areas subject to floods, landslides, and other risks.

The first question is whether you can subdivide at all. Many small lots of under an acre cannot be subdivided in many jurisdictions. Older lots may be governed by less restrictive regulations under “grandfathering” provisions.

If you are allowed to subdivide, then the minimum lot size, minimum frontage, allowable lot coverage (of buildings and impervious surfaces), house size, perc testing, number of bedrooms, setbacks, and other requirements will all be governed by local zoning regulations, which can vary a great deal from one town to the next.

If the wish to develop a portion of the land that is considered a critical area, development rules are likely to be more restrictive and may limit other activities such as clearing and tree cutting.

The place to start is with your local department of building and zoning. Schedule a meeting with your local zoning official and describe what you hoping to do. They can tell you what is allowable and zoning rules will apply. In some cases, a special permit or variance is required, which can be expensive or impossible to obtain, depending on circumstances.

You can also do a lot of preliminary research online nowadays. Zoning maps, zoning laws, and state laws are generally posted online, but it is not always easy to decipher the technical terms sometimes used. A surveyor could help if you wish to bring in an expert at some point.

Caroline says

Can I Add Exterior Stairs to 2nd Floor?

I own a 2-story single-family dwelling built in the 1920s. It was inspected by the city in 2012 and all that was present then was approved and signed off on. That includes two bedrooms with closets and a full bath and “wet bar” (counter with a sink) upstairs. My question is about an exterior stair case that used to be there. It had a landing at the top, where one could enter the second story through an ordinary door. Inside the house, there is another staircase that goes from a first floor hallway to the second story. Given the existing interior stairway, can this house, as a single-family dwelling, have an exterior staircase that goes to the second floor? The house is in a city in Los Angeles County. What code governs topics like this one?

buildingadvisor says

Typically, whether or not this type of stair would be allowed would be governed by zoning. The actual construction details of the stairs, including tread and riser size, handrails, total height, etc., would be governed by the municipal building code. In general, zoning will not permit changes to a single-family dwelling that would makes it function as a multi-family dwelling with separate living spaces. This might include adding a separate entrance, second kitchen, etc.

Both building codes and zoning regulations are adopted, interpreted, and enforced at the local level – town, city, or county, although in some cases state regulations preempt local rules.

In situations where public safety is not an issue, existing construction is often grandfathered and allowed to stay. However, once the stairs were removed, you would probably lose any rights that were grandfathered. This can get complicated, since some towns allow lots to be developed under the zoning regulations in place when the lot was originally subdivided and deeded. The specifics depend on your local regulations and the way they are interpreted by the local building and zoning departments.

When it doubt, it’s always best to schedule a face-to-face meeting with the local dept. of building inspection with drawings, photos, or other documentation of what you are trying to do and ask whether it will be allowed or not, or whether it might be allowed with a special permit or variance. These folks appreciate being consulted beforehand and are more likely to be cooperative if they are brought in to the process early. If a special permit or variance is required ask how to apply, and what is the likelihood it will be granted.

In a large urban area like LA county, applying for a special permit or variance can be very complicated and expensive and may require the help of a lawyer to be successful. A lawyer can also tell you whether it is worth the time and money to pursue

Peggy says

Setback for Driveway?

What is the minimum distance required from my property line that the neighbors could put a driveway. The new driveway has a concrete pipe for a drainage ditch as you come off the state road? There has never been a water problem in the shallow ditch beside the shoulder of road, so I’m not sure why they are redoing the driveway.

buildingadvisor says

Side-yard setbacks for driveways, houses, and other structures are determined by local zoning regulations, which vary greatly from town to town. So you really need to check with your local building and planning department. If you are in a subdivision, it may also have rules more restrictive than town zoning.

The rules for driveway placement can be pretty complicated. Many towns allow driveways to be on the lot line, while some require setbacks of 2 ft. to 10 ft. or more. Most towns with zoning regulate the minimum and maximum width of the driveway and how far parking spaces must be from front and side lot lines. It’s always best to check with the town before proceeding with work.

If your neighbors are replacing an existing driveway in the same location, most likely the location is grandfathered and not subject to any new zoning laws.

Not sure about the pipe, but it sounds like it is there to allow water to flow freely below the road surface through a culvert – a good idea.

Leonie K. says

Discovered Setback Violation During Sale

We are currently in the process of selling our home in South Florida. During the inspection period it was discovered that a corner of the building is encroaching on the setback (by about 1 foot). The lot is triangle shaped. We are now trying to figure out how we can remedy the situation so we can convey marketable title to the property. Is a variance application the only solution? Thank you and best regards

buildingadvisor says

Setback regulations and their enforcement varies from one municipality to another, so it is difficult to say what is your best remedy.

It is possible that the plan was originally approved via a variance or “special permit”, which should be uncovered in a title search. It is also possible that the building complied with the existing setback regulations at the time of construction, in which case the building would be grandfathered. Permits and other documentation should be in the public record, but it might take a real estate lawyer to uncover them.

More likely, however, the encroachment was an oversight by the builder. In that case, a setback variance may be required. There is a good chance that a variance (or a “special permit” which is easier to obtain) would be granted in your instance. However, the process of applying for a variance can be onerous and time-consuming.

You should start by speaking with your local planning and zoning department about the process, timing, and likelihood of getting your nonconforming house plan approved retroactively. I would also speak with a local real estate lawyer, to get his perspective, along with his cost estimate for proceeding. While it is possible to apply for a variance on your own, an experienced lawyer can certainly speed up the process and improve your chances of success.

If you can find a cash buyer willing to purchase the property with this title defect (at a discount) that might also be an option. A mortgage lender, however, might balk at loaning money until this issue is resolved.

You can find a good overview of setback regulations at the legal self-help website Nolo.com.

jake says

Can Abutter Build Commercial Building?

I live on 18 acres, mostly rock/clay and the perk tests were originally for three-bedroom house. Next door is 18 acres, just sold to a company which plans to expand a 3-4 bedroom to 10-12 for commercial use. Is this possible? In this day and age are we going backwards? Or is payola still as good as Bitcoin?

buildingadvisor says

In general, what your new neighbors can build depends primarily on zoning and health department regulations. Zoning would cover the size and type of building and its usage; the health department would regulate perc testing and on-site sewage.

If they are building outside of the zoning rules, they would need a variance. As an abutter, you should have been notified if they applied for a variance, and been given a time-frame to appeal.

If their planned use is allowed by zoning, they still would need approval for the commercial-sized septic system (unless they are tying into a municipal system). Maybe they got approval for an “alternative” system, which are allowed now in many areas.

All of this is a matter of public record, so you might want to pay a visit to the local zoning and building department to find out what the deal is. The folks there can sometimes be a great help.