Q: Is prefinished hardwood flooring as good as traditional hardwood? We are remodeling and wish to install hardwood strip flooring. We are considering unfinished hardwood flooring, prefinished solid hardwood, and laminated hardwood that is about 3/8-inch thick. We are leaning toward unfinished but have read that some of the prefinished products have better finishes. What’s your advice? Also, which is better oil- or water-based floor finishes? – Jake

A: For the absolute best floor, there is nothing like 3/4-inch hardwood, nailed in place, sanded, and finished with at least three coats of oil-based urethane. This is also the most expensive option, the slowest, and the messiest in a remodel due to the sanding.

However, an experienced professional should leave few traces of sawdust. If they use floor sanders with integrated vacuum systems, you should have virtually no dust. You can save money by using standard dust collection and poly sheeting to isolate the refinishing area. We had two floors refinished in this way with no residual dust.

One advantage of a solid wood floor is that it can be re-sanded and refinished multiple times, but a good finish should last 10 to 20 years depending on usage. If only a small area is worn, a good refinisher can be spot repaired by lightly sanding the damaged area and blending in the new finish.

As for water- vs. oil based finishes, oil is definitely harder and more scratch resistant. Water-based finishes have come a long way, but are not as durable in my experience. Water-based finishes dry much faster with minimal fumes and will not darken or develop a yellowish patina over time. If you want your floors to stay nice and bright, consider water-based urethane. But plan to take off your shoes and use furniture pads – a good idea anyway with wood floors.

Prefinished wood floors are also a good option. You can buy full ¾-inch strip flooring pre-finished as well as thinner laminated products. Laminated wood flooring is usually about 3/8-inch thick and either nailed (and/or glued) or floating. Here are the pros and cons:

Pre-finished ¾-inch strip flooring. Installs quickly with no sanding required so the installed cost is usually less than traditional hardwood finished in place. Many finishes are available, some claiming to be superior to field-applied urethane. There will always be a small V-groove at each flooring joint to accommodate the tiny variations in wood thickness from one board to the next.

Dirt can accumulate in the V-grooves, but most prefinished flooring now uses small “microbevels” that minimize this problem. Still, prefinished flooring will not provide the seamless surface of traditional hardwood. Full-thickness flooring can be refinished like traditional hardwood and the micro-bevels will be gone.

Fully attached laminated strip flooring. Where height is an issue, thinner laminated wood flooring is a good option. Sometimes called engineered wood flooring, laminated strips or panels are usually nailed or stapled in place, sometimes with glue as well. Do not confuse this with “laminate flooring” which is plastic laminate with a wood-grain or other textured finish. This material is essentially the same as plastic-laminate (Formica) countertops.

With wood laminate flooring, the thickness of the top wear layer is important as well as the type of wood used in the substrate. Look for a wear layer of at least 1/8 inch. A thin top layer may not be suitable for refinishing and may be vulnerable to denting. This is especially true if softer wood is used for the inner core. Even though the top 1/8-inch is oak, it will easily dent if softer wood is used underneath. As with solid flooring, many different finishes are available, some harder and more durable than others.

Because it is an engineered product with cross laminations, laminated wood flooring is more dimensionally stable than solid wood. This means that beveled edges are not required, although some products still have these. Laminated flooring is the best choice for glue-down installations, for example, over a concrete slab. Also the material is a better choice for high-moisture areas such as finished basements or applications subject with wide swings or moisture or temperature such as radiant floor heating.

Floating hardwood floors. Another option is to leave the flooring unattached to the underlayment – a so-called floating floor. You can float a floor over any stable substrate, including wood, vinyl, concrete, or smooth tile. A floating hardwood floor is the least expensive option.

With most floating floors, the pieces are edge-glued to one another and installed over a thin layer of high-density foam and a vapor barrier. Newer “click-lock” flooring locks together with no glue, making this a good DIY project. A floating floor is more resilient underfoot than one glued to concrete, but feels less solid than a nailed or glued floor.

Special details are needed at edges to accommodate movement. This is usually hidden by baseboards, but requires special moldings at door openings and other transitions. Restraining the flooring ends at doorways or the room perimeter can lead to open joints or buckling.

Because there are no mechanical fasteners, floating floors rely on good quality flooring and a very flat slab or subfloor to produce a smooth, trouble-free floor. Look for the flooring materials that are straight and uniform in thickness, fit together snugly, and lay flat with few visible gaps. The subfloor should be level to within 1/8 inch over 10 feet. If necessary, shim low points with clean mason’s sand or rosin paper layered in the low spots to create a tapered shim.

Floating floors are suitable for basements and other high-moisture areas as they tend to expand and contract as a unit. They are relatively easy to install and to remove. They cannot be sanded like a conventional hardwood floor, but some can be lightly sanded and refinished or coated with no-sand finishes. – Steve Bliss, BuildingAdvisor.com

Choosing a Species & Grade

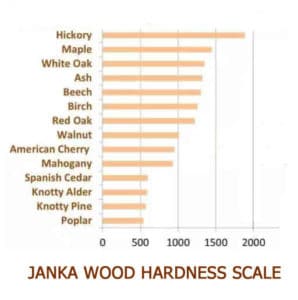

Most hardwoods are hard and dense enough to withstand the normal bumps and bruises of everyday use. The most common species — red oak, white oak, and maple — are all extremely hard and durable. Ash is also very hard and hickory is about the hardest domestic hardwood in common use. Birch is moderately hard and durable.

Softer hardwoods use for flooring include walnut and cherry. Both are very attractive but not the best choice for high-traffic areas.

Every wood has a rating on the Janka Hardness Scale, which provides an easy way to compare how well a wood species resists denting from impacts.

Otherwise, choosing a species is largely a matter of taste and budget. Remember that most woods will change color over time, so look at an aged piece with the type of finish you are using. Cherry darkens a great deal from exposure to light, so a section under a carpet will not match the rest of the room.

You can often save a lot of money by choosing a lower grade of wood. This will have more color variation and more “figure,” meaning streaks, marks, and distinctive grain patterns. Some people (like me) find this attractive. With certain species, such as hickory, a lot of figure and color variation are a basic characteristic of the wood species.

Leave a Reply