In This Article

Performance

Choosing a Housewrap

Draining Housewraps

Stucco

Installation

Door & Window Details View all EXTERIORS articles

Referred to in the building code as a “water-resistive barrier,” the main goal of a sheathing wrap or housewrap to keep liquid water out of the structural part of a building. At the same time, the sheathing wrap must allow water vapor to pass through so the framing and sheathing can dry to the exterior if it gets wet.

Fortunately a number of materials, including traditional asphalt felt (tar paper) have this ability to stop liquid water while remaining “permeable” to water vapor.

Types of Sheathing Wrap

All sheathing wraps fall into three basic types: asphalt felt, Grade D building paper, and synthetic housewrap.

- Asphalt felt (tar paper) was the the traditional choice of builders for many years and still has some advantages over newer alternatives.

- Grade D building paper is used primarily under stucco in the western United States and is essentially a lighter-weight version of asphalt felt.

- Housewrap refers to the wide variety of synthetic sheathing wraps widely used today. Originally over-sold as energy-savers, their main function is the same as other sheathing wraps – to keep out liquid water out of the structure, but let water vapor pass through to allow wet buildings to dry out.

Comparing one sheathing wrap to another is difficult since there is no single test standard for all products, and even where manufacturers follow the same standard, test conditions may vary dramatically from one company to the next. More important may be the material’s ease of installation and durability over time. Some of the synthetic products look great on the day of installation, but degrade quickly when subjected to prolonged wetting or exposure to UV.

In my experience, traditional 15lb. asphalt felt often outlasts the synthetic housewraps, especially where it remains wet for extended periods. Under prolonged wetting, plastic housewrap tends to deteriorate. Another advantage of traditional asphalt felt is that it can absorb excess moisture and release it later when drying condition improve.

Performance Characteristics of Sheathing Wrap

In order to be accepted by code as a “water-resistive barrier,” a housewrap must meet specific measures for permeance to water vapor, resistance to liquid water, and air infiltration.

Permeance. Permeance ratings measure the rate at which water vapor (as opposed to liquid water) passes through a material. In general, a sheathing wrap should have a permeance of at least 5 perms, similar to dry asphalt felt. High permeance allows wall assemblies to dry out should they get wet. Plastic housewraps range from around 5 to over 50 perms. Since common sheathing products like ply¬wood and oriented-strand board (OSB) have permeance ratings of less than one, the sheathing is more likely to interfere with drying than the sheathing wrap.

Water Resistance. There are several ways to measure the ability to stop liquid water from passing through. In general, products with high permeability, such as perforated housewraps, do less well on water resistance tests. In practice, however, all approved sheathing wraps do a good of shedding liquid water in an actual building.

Air Infiltration. Many sheathing wrap suppliers tout their products’ ability to block air infiltration, often citing proprietary test results. Some follow ASTM E283, in which an 8-foot-square wall section is tested before and after installation of the sheathing wrap. However, since the manufacturer is free to specify the type of wall assembly, one test is not comparable to another, and none simulates real job-site conditions with seams and holes in the sheathing wrap.

If a house already has a reasonably tight wall assembly, there is little evidence that a layer of housewrap will significantly tighten the building. In general, air-sealing efforts are better spent on the building’s interior, using caulks and gaskets or a continuous polyethylene air/vapor barrier.

Choosing a Sheathing Wrap

In comparing sheathing wraps (also called sheathing paper and housewrap), you can look at a lot of technical specs regarding permeance, water resistance, and air infiltration. Unfortunately, these tests don’t tell us too much about real world performance. Also companies tend to use the test protocol that favors their product over their competitors.

The good news is that, installed carefully, any of the sheathing wraps can perform well as an effective barrier to water penetration. Other important factors to consider are how long will they last under adverse conditions (for example, when wet, hot, or exposed to UV for extended periods) and how quickly they will let a wet wall dry out.

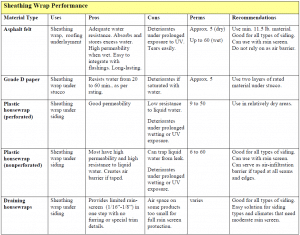

The three main choices are traditional asphalt felt, Grade D building paper, and the newer plastic housewraps. The optimal product will depend upon the siding choice, building details, and climate. With any sheathing wrap material, however, the key to good performance is to carefully lap the material to shed water. This job has been made easier by the introduction of a number of peel-and-stick membranes for use around windows, doors, and other trouble spots. General performance characteristics of sheathing wraps are summarized in the Table below (Click to Enlarge).

What’s a Perm, Anyway?

Although numbers can be misleading, it’s useful to understand the basics of permeance. Permeance ratings, measured in perms, indicate the rate at which water vapor will pass through a material when the humidity is higher on one side. This indicates how quickly water can dry out if blocked by this material.(Technically speaking, one perm = one grain of water vapor passing through 1 square foot per hour per inch difference in vapor-pressure).

In general, a sheathing wrap should have a perm rating of at least 5 to enable walls to dry out in a reasonable period of time should they get wet. Traditional sheathing wraps such as asphalt felt and Grade D building paper (used under stucco) both measure about 5 perms. Plastic housewraps range from around 5 to over 50 perms.

By comparison, common sheathing materials like OSB and plywood have perm ratings of less than one, so they would slow down drying. Other sheathing materials that can trap water in a wall are

- Foil-faced panels: Vapor impermeable

- Extruded foam insulation (XPS), such Styrofoam and Foamular: perm rating of 1 for a 1 in-thick material; 0.5 for 2-in. thick panels.

- Expanded foam insulation (EPS), often called “beadboard”: per rating of about 3 for -1-in. panels, 1.5 for 2-in.

Asphalt Felt. The old standby, often called “tar paper,” allows drying with a perm rating of of approximately 5 (more when wet) and blocks water effectively on a vertical wall, making it an effective sheathing wrap . The modern felt papers are made from recycled cardboard and sawdust rather than traditional cotton rags, but have similar properties. Like older felt paper, the substrate is saturated with asphalt or bitumen.

Asphalt felt has other desirable qualities as well. If water leaks into a wall, the asphalt felt will tend to soak up the excess water (as will lumber and wood products like plywood), helping to store the water until drying conditions improve. Also, once wet, the permeability of asphalt felt actually rises from 5 to as high as 60, further promoting rapid drying. This is the same characteristic engineered into some of the hi-tech “smart” sheathing wraps. In contrast, plastic housewrap does not absorb water and tends to trap liquid water (although it will permit slow drying by letting water vapor pass through).

While plastic housewraps now dominate the market, some contractors have returned to asphalt felt as a weather barrier on sidewalls. In addition to its good water-management characteristics described above, some people find that felt paper is easier to install because of its rigidity and narrow 3-foot roll width and easier to properly tie into flashings. Felt, however, will tear if not handled carefully, and tends to get brittle and deteriorate from UV if left exposed to sunlight for

extended periods. Otherwise, asphalt felt remains a good option for modern homes.

However, remember that what is sold as #15 felt today is typically half the weight of traditional 15-lb. rag felt, which weighed – guess what — 15 lbs/square (100 sq. ft.)! Nowadays, unrated #15 felt can weigh as little as 7.6 lbs/square. Unrated #30 felt typically weighs 16 to 20 lbs/square.

Also, the quality and durability of unrated felt can vary a great deal. To get a heavier weight product that has been tested to meet quality standards, you need to buy asphalt felt that is labeled to comply with ASTM D226 or ASTM D4869. Products are tested for weight, strength, pliability, and other characteristics. Weight per 100 sq. ft. are as follows:

Under ASTM D226:

#15 Type 1: 11.5 to 12.5 lbs

#30 Type 2: 26 to 30 lbs. (ASTM D226 –#30 Type 2

Under ASTM D4869

Type 1: 8 lbs. (min)

Type 2: 13 lbs. (min)

Type 3: 20 lbs. (min)

Type 4: 26 lbs. (min)

Grade D Building Paper. Grade D building paper is an asphalt-impregnated reinforced paper, similar to the “kraft” paper backing found on fiberglass insulation. Unlike asphalt felt, it is made from new wood pulp, rather than recycled material. Grade D paper is commonly use is under stucco in the western United States. The vapor permeance of Grade D paper is similar to asphalt felt and it blocks liquid water effectively in tests for anywhere from 10 to 60 minutes.

However, in the real world Grade D paper tends to deteriorate when wet for extended periods. To protect against leakage in traditional three-coat stucco, contractors often use two layers of 30-minute paper. Because the paper layers tends to wrinkle when installed, the two layers form a small air space that some claim creates a protective rain screen. In a wet climate, however, a true rain screen is preferable using a plastic drainage mat.

Plastic Housewrap. There are a wide array of plastic housewraps on the market. Most are nonwoven fabrics made from polypropylene or polyethylene. Some are engineered to allow water vapor to pass through the material, while others have small perforations to let water vapor through. Because there are several testing standards for plastic housewrap that yield very different results, it is difficult to make apples-to-apples comparisons. However, several field studies and published test data suggest the following:

Permeance to water vapor. In general, non-perforated housewraps (Tyvek, Amowrap, and R-Wrap) are considerably more permeable to water vapor, ranging from 48 to 60 perms, than perforated housewraps. Typar, a popular non-perforated material, is rated at 9-15 perms.

Water resistance. All sheathing wraps, including asphalt felt paper, will effectively shed water on vertical surfaces. Pooled water, however, will leak through most perforated plastic housewraps over time, while the nonperforated materials will contain liquid water indefinitely.

Damage from extractives, stuccco, and moisture. Researchers have reported that extractives leaching out of redwood and cedar siding can cause plastic housewrap to lose its water repellency and to deteriorate. Back-priming the wood siding or leaving an air space behind the siding will help prevent this. Stucco will also degrade plastic housewrap and is rarely installed over it. Details that trap water against the housewrap, or catch water in folds, such as poorly designed window openings, promote rapid deterioration of the housewrap.

Energy efficiency. When first introduced, plastic housewraps were heavily promoted as an energy-conservation product, based on some questionable data showing that they reduced air leakage rates when installed with great care on a very leaky house. In real world applications using standard building techniques, there is little evidence that housewrap will significantly improve a new building’s energy performance. It is possible to use housewrap as an effective exterior air barrier, but this would require extensive taping and sealing, and proper detailing at all penetrations and transitions to other materials.

Recommendations. Given their high perm ratings and ability to block liquid water, the non-perforated housewraps are a good choice for most building applications, with the caveat that careful detailing is required to prevent water being trapped in folds or wrinkles of housewrap at windows, corners, and other transitions. Waterlogged plastic housewrap with deteriorate pretty rapidly. Prolonged exposure to UV during construction can also shorten the life of plastic housewraps.

Traditional asphalt felt is also a good option and may outlast plastic housewraps over the long run.

Many contractors find the 10-ft-wide rolls of lightweight plastic housewrap more convenient to install than heavy 3-ft-wide rolls of asphalt felt. Also plastic housewrap remains flexible in the cold and is less likely to tear than felt paper. Some find the narrow width and greater rigidity of asphalt felt an advantage. Either material can perform well if installed correctly.

Draining Housewraps

With growing interest in rain screens, manufacturers have responded to the need for an air space and drainage plane with a variety of plastic housewrap products that are either wrinkled or corrugated to provide an integrated air space. These are either wrinkled or corrugated to provide an integrated air space. These include products developed primarily for stucco, such as DuPont StuccoWrap, Fortifiber HydroTex, and others developed for use under a variety of sidings. These include ( in alphabetical order):

- Benjamin Obdyke Hydrogap: vertical spacers, 1 mm (.040”) gap

- Dupont Tyvek DrainWrap: vertical channels, .004” thick

- Fortifiber WeatherSmart Drainable, dimpled

- Kingspan (formerly Pactiv) RainDrop 3D: vertical channels .020” thick.

- TamlynWrap Drainable Housewrap: horizontal spacers 1.5 mm (.060”) gap

- Valeron Vortec: non-directional channels, .003” thick

The small air space created by these products generally range from as little as 1/10mm to 1 or 2 mm (1 mm = 4/100 inch) in.). Although these materials may allow for a capillary break and some drainage it is unlikely that they will provide any measurable airflow to promote drying.

Some types of siding with many nails, such as cedar shingles, may compress the materials, further reducing the protection provided by the narrow space. While some manufacturers have test data supporting these products, the jury is still out in terms of long-term performance on homes.

In wet climates, or wherever better drainage and ventilation are needed, a minimum 3/6 to 1/4 in. (5-6 mm) drainage gap is recommended by most experts. To achieve this, most builders use wood or plastic furring strips.

Another option is a plastic drainage mat that installs over the weather barrier. Benjamin Odyke’s HomeSlicker, which comes in 3mm and 10mm thicknesses, is available laminated to Typar , providing a one-step installation like the draining housewraps, but with a more reliable rainscreen.

Read more about Building Rain-Screen Walls.

Stucco Underlayments

Stucco has special requirements for underlayment because it tends to absorb and hold a lot of moisture, which can migrate into the sheathing and wall cavity. Also the cement material will degrade plastic housewraps if in direct contact. For that reason, most building codes require that stucco be applied over two layers of Grade D Building Paper (described above) or traditional asphalt felt.

Grade D paper is used primarily in the western states, while the rest of the country uses asphalt felt — more for matters of tradition than building science. Grade D paper is thinner and easier to work with, but more prone to deteriorate if saturated with water. Also Grade D paper seals poorly around nail and staple penetrations.

Traditionally, 3-coat stucco was applied to metal lath nailed over asphalt felt with with special furring nails that spaced the lath about 1/4 inch from the underlayment. This created a capillary break that helped protect the underlayment and slowed the migration of water inward. In older, uninsulated homes, this was adequate as any water that penetrated the stucco would have a chance to dry out before doing any damage to the framing.

Modern insulated walls with vapor retarders, and foam sheathing in some cases, do not dry out as quickly. Consequently, moisture-related wall damage is much more common today. In cool, wet climates, stucco walls have had a high rate of failure. This is due to a combination of climate conditions, wall details, and construction techniques. For example, the use of staples to attach the wire lath has lead to greater leakage and the loss of a capillary break.

Also water leakage around windows has been a big problem for stucco and nearly all type of siding. The industry is still not in full agreement about the best way to flash and seal and flash around windows.

Arid climates such as Southern California are much more forgiving than cold and wet climates, like in Minnesota, where a rash of stucco failures have been documented. In difficult climates, the safest approach is to use a rain-screen wall, with a drainage layer between the underlayment and the metal lath. A number of plastic drainage mats are available for this application, such as Stuc-O-Flex Waterway or MTI Sure Cavity.

If a plastic housewrap is used as the water-resistive barrier (as required by code), make sure the second layer is Grade D Building Paper or asphalt felt, which have better resistance to cementitious materials.

In recent years, a variety of specialty underlayments for stucco have been introduced. Some, such as Fortifiber’s Two-Ply Super Jumbo Tex 60 Minutes combine a water-resistive barrier with a drainage layer, simplifying the installation. Any product other than Grade D or asphalt felt needs approval from the local code even if it has test reports documenting its performance. So check first with your local building department.

Sheathing Wrap Installation

The main purpose of the sheathing wrap, whether building felt or plastic housewrap, is to prevent water leakage into the building structure. It is critical, therefore, to cover the entire shell from roof to foundation, including gable ends and band joists, and always to lap upper layers over lower layers, shingle-style, to shed water. It is also critical to correctly weave the sheathing wrap into all wall flashings, paying special attention to the flashings around windows, doors, and other penetrations in the shell.

.

Shingle Principle. While the technical ratings of sheathing wraps vary significantly, how they are installed is far more important than the specific product used. The key is to always lap the joints in sheathing wrap so water always flows away from the building and on top of the layer below, shingle style.

Equally important is to properly detail all areas where sheathing wrap meets flashings, especially around door and window openings. The same Shingle Principle applies: Materials should always be lapped to shed water over the top of the layer below – always directing the water away from the building – never into the structure.

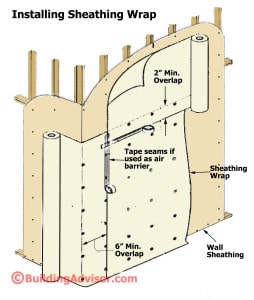

Code Requirements. The building code (International Residential Code) requires that all new homes have a “water-resistive barrier” which in practical terms means a waterproof barrier behind the exterior cladding. According to the code, the barrier should consist of a weather-resistant sheathing paper lapped at least 2 inches horizontally and 6 inches vertically. It also states that sheathing paper be properly integrated with the flashings used around doors and windows and other penetrations or intersections with other materials (see Illustration).

All new homes must have a “water-resistive barrier,” on the exterior, typically sheathing wrap or felt paper. Lap either material at least 2 inches horizontally and 6 inches vertically. The sheathing paper must integrate properly with window and door flashings, a common source of water intrusion.

The sheathing paper specified by code (IRC) is ASTM-rated Type 1 paper (ASTM D226), an asphalt-saturated felt (tar paper) which weighs a minimum of 11.5 pounds per square. Most of the felt paper stocked by lumberyards today is either unrated #15 felt, which typically weight around 7 or 8 lbs. per square (100 sq. ft.) or unrated #30 lb. felt which weighs 15 to 20 lbs. per square. (Lumberyards often call these items 15 lb. and 30 lb. felt, a holdover from the old days when that what they actually weighed.) In most parts of the country, ASTM—rated papers must be special ordered.

As with most code provisions, this one allows other materials accepted by code authorities as “equivalent.” Most plastic housewraps on the market, such a Tyvek, Typar, Barricade, and a slew of others have all passed muster with the IRC as equivalent to Type 1 building paper.

Detailing at Windows and Doors

Leaks around doors and windows account for a large number of construction failures nationwide, often costing thousands of dollars to repair and the source of many large lawsuits in condominium and other multifamily projects. Often the problems are hidden behind exterior finishes for years, only to show up when the house or unit is being sold or remodeled. Flash doors and windows correctly the first time or you can expect big headaches down the line.

The main problem is that both windows and wall construction, and the flashing materials, themselves, have all changed dramatically over the past 30 years, but finding a reliable, industry-standard way to integrate the various components is still a work in progress.

With modern flange-style windows and doors, detailing flashings and sheathing wrap to shed water is easier said than done, so it pays to use use the best materials and techniques here. The materials used to seal around openings should last for the life of the building – or at least the life of the siding and windows. Never rely on caulks and sealants here – they will not last more than a few year. Cut corners here and you may end up tearing out your windows and the surrounding finishes long before their time, and you may find extensive damage to the windows and surrounding framing.

The code also allows alternative water-resistive barriers that are “code-approved” as equivalent to felt. This includes all the leading plastic housewraps. The housewrap manufacturers recommend 6 to 12 inches of overlap at vertical seams and 4 inches at horizontal laps, with all joints taped.

With plastic housewrap, you should wrap corners at least 6 inches each way. If the walls are sheathed and wrapped before being raised, leave a 6- to 12-inch overlap at one side of each corner, and leave a 12-inch, unstapled flap at the bottom to cover the band joist area after the sheathing is nailed off. Wide staples with a minimum 1-inch crown are recommended every 12 to 18 inches for plastic house-wraps.

Read more on Window Flashing Details

Richard says

I am adding a potting shed (combination shed/greenhouse) onto a existing shed which has traditional felt under lap siding and asphalt roof shingles. Being that the inside is likely to get humid at times I am thinking 30wt felt would be best for the roof and walls (vs synthetic) as your article states it absorbs moisture and has a higher perm when wet. Am I accurate with this assumption.

Thanks

buildingadvisor says

Felt Paper vs. Synthetic Housewrap?

Don’t have a lot of info about climate, insulation, interior or exterior finishes, or other building details.

But, in general, yes, asphalt felt would be a good choice. If you can find it locally, ASTM-rated felt is much better than unrated felt, which does not need to meet any standards of thickness or quality.

That said, the sheathing wrap that you use is only one component in your management of interior and exterior moisture. A good air barrier and vapor retarder on the interior, adequate ventilation, and properly detailed flashing on the roof and walls, and windows, are equally important.

Also, you get a lot of mileage from roof overhangs, which keep rain from dripping down the sidewalls, leading to wear and tear and potential lekage.

Mark O’Conner says

Best Moisture Barrier for Masonry Walls?

I am looking for a sheeting moisture barrier to be used for covering large cinder block structures in a high humidity and high moisture climate. Thank you,

Mark

buildingadvisor says

Unlike a wood-frame wall, a masonry wall is unaffected by moisture. Most are also very permeable to water vapor – it passes readily through concrete and concrete block (sometimes referred to as “cinder block”). It also porous and will absorb and store water.

Not sure what you are building, but assuming that this is living space that is conditioned – heated and cooled – you will want to keep exterior water reaching from the block.

What material is best will depend on the exterior cladding, type of insulation, interior finishes, and the construction details of the wall.

When clad with brick veneer, stone veneer, or other systems that stand away from the block wall, the most common moisture barrier (“water-resistant barrier” in current codes) is asphalt-felt. If you use this, look for ASTM-rated felt which is heavier and more durable than unrated materials.

Under stucco, you can use asphalt felt or two layers of Grade-D building paper, commonly used on the West Coast.

Both asphalt felt and Grade D paper will block liquid water but allow water vapor to pass through. This is helpful when the wall has to dry to the exterior, but can cause problems in certain situations – notably with brick veneer, stucco, fiber-cement, and other masonry materials that can store a lot of moisture.

When the sun beats down on a wet masonry wall, it can drive the moisture inward, ultimately condensing on the first cold surface – sometimes that’s the back of the vinyl wallpaper in a air-conditioned building.

To prevent this type of problem, you need a well ventilated cavity behind the brick veneer or other cladding, such a vented rain screen. Where a vented cavity is not an option, then a moderate vapor retarder is recommended. This could be a layer of unfaced foam insulation, or a sheet or liquid applied vapor retarder.

If the vapor retarder is also intended to serve as an air barrier, reducing infiltration of outdoor air into the building, then it will need to be taped at seams and sealed around the perimeter. Another option is to use the drywall or interior foam insulation (taped and sealed) as the air barrier.

Matthew Bruce says

What’s Best: Tyvek or Felt Paper?

I’m purchasing a house that currently has vinyl siding. With log being our dream home, we are tearing down the vinyl and putting up 2×8 cedar log siding. What is the best underlayment for this situation? It’s in the Northeast Catskill mountains a wide variation of weather. I’m not sure what type of wrap is underneath the vinyl but I’m assuming to just replace it as it’s 15 years old. I’ve been reading that there’s evidence the synthetic wrap like Tyvek deteriorate when under wood like cedar. I was thinking of going with 15 or 30lb felt but I’m just not sure. Do I put new flashing around the widows and doors?

buildingadvisor says

There are a lot of sheathing wraps on the market and it’s hard to say which is the best. Some haven’t been around that long and no one has done any comparative testing to my knowledge.

en around the longest and has established a good track record, especially ASTM-rated felt, which has to meet certain standards for materials and thickness. Unrated, home-center, felt paper is far below its advertised weight of 15 or 30 pounds per square (100 sq. ft.).

Tyvek has been around, as a sheathing wrap, since the 1970s (before that it was used mostly for tear-proof envelopes). I’ve seen Tyvek break down and fall apart within 5 years where it was bunched up around a window and trapped moisture. Under very hot conditions, I’ve seen it become brittle after a number of years, but still holding together – the house was about 35 years old.

Since all plastic housewraps are variations on a theme, they may not last for the life of a house, but if installed properly, and not exposed to the UV radiation for too long when installed, they will probably last as long as most sidings.

The tannins in cedar and other resinous wood can harm housewraps if the back of the siding gets wet — as it usually does at some point. Some people say cedar can harm asphalt felt as well. The best solution is to back-prime the cedar siding and, if possible, leave an air gap between the siding and housewrap.

The air gap also provides a drainage plane. This is called a rain-screen wall and it will increase the life span of both the housewrap and the siding. Most wood today is not of the same quality as it was 30 years ago, so rain-screen construction is becoming more common.

And, yes, you absolutely have to flash around windows and doors – that’s where the water usually gets in. The window and door flashing must be integrated with the housewrap so that water always flows away from the building as it flows downward. This is called “shingle-style” as it is the way roofing and sidewall shingles keep water out of your house. The same applies to flashing.

Sounds obvious, but you’d be surprised at home many people mess this up and install flashing that directs water into the building, not away from it! So time spent planning and installing the window flashing is time well spent

Lawrence says

Best Underlayment for One-Coat Stucco?

Just wanted to get your opinion on house wraps under stucco finishes. I am building in El Dorado Hills and using what’s called an Omega One-Coat Stucco finish. My plans call for a double wrap of Tyvek house wrap over the OSB. The Stucco contractor says two layers will trap mold. He suggests one layer Tyvek or something better and one layer of Felt or Stucco type paper over that. I’m 20 mi. east of Sacramento, CA, but it is hot and arid a lot of the year. Our climate zone is 12. Any suggestions on a building wrap whether it’s one or two layers? This will be my Last house so I don’t want to regret my choice. Thanks.

buildingadvisor says

Your stucco contractor is correct that applying stucco directly to Tyvek or other plastic housewraps is a bad idea. I’m not sure about trapping mold, but it’s been shown that masonry materials such as stucco can cause plastic housewraps to deteriorate. I’ve also seen Tyvek deteriorate rapidly where it was poorly detailed (bunched up) and trapped water. The idea that Tyvek lasts forever because it is plastic just ain’t so.

The industry standard for two-coat stucco underlayment, at least on the West Coast, is two layers of Grade D building paper. It’s also acceptable to place one layer of Grade D building paper or asphalt felt over a layer of Tyvek. For a proprietary one-coat stucco, I would check to see what the manufacturer recommends to make sure you don’t void the warranty.

One-coat synthetic stucco products such as Dryvit have had a checkered past. They can work fine, but the devil is in the details. I would use one-coat stucco with caution and make sure you follow the manufacturer’s recommendations to a T. Pay special attention to detailing around windows and other openings and transitions, as well as the weep screed at the bottom of the wall.

There are a number of specialty housewraps developed specifically for stucco that provide a drainage plane under the stucco finish. However, if you want to use one of these, make sure the product is approved by your local code as well as the manufacturer of the stucco finish.

Read more on Stucco Underlayments

Chris M Benoit says

Lawrence, consider a Rainscreen with a Filter fabric like SLicker Max, the fabric keeps the mortar/scratch coat out of the rainscreen matrix and the Rainscreen allows for drainage and drying.

Donnie Vick says

Is Felt Paper a Good Choice for Walls?

Hi,

I’m building a 10×12-ft hobby room behind my house. The 12-year-old shed structure was disassembled from another property that was being torn down. When I took it apart, the felt paper was in excellent condition. There was no water damage or water marks on any of the exterior plywood and the shed was dry as a bone. I live in Clearwater Florida, 5 miles from the Gulf of Mexico. After reading this and seeing how well it held up before; I’m going back with felt. I don’t know the thickness of what I took off was, but was hoping you could tell me what thickness would be best for my new project and what type of fastening device/nail would be best? The previous builder used standard roofing nails on the felt. I’m either using composite siding, or vinyl over the felt. Thanks!

buildingadvisor says

Hi Donnie,

Asphalt-saturated building felt has been used for decades and has an excellent track record. It holds up very well to moisture and extreme temperatures. In fact, I just installed a new roof and asked the roofer for ASTM Type 15 felt rather than the synthetic they now prefer. He liked the synthetic, he said, because it provided good traction for working, but he took it on faith that it would last. He couldn’t tell me what the material was or how long it would last other than “something like Tyvek, only much better…”

The standard weather barrier used traditionally under wood, vinyl, and other siding materials is 15-pound felt. For stucco, the standard is two layers of Grade D building paper.

Nowadays, low-cost “#15” felt can weight as little as 8 to 12 pounds per square (100 sq. ft.). This might be fine for a shed, but if you want a product that will last, you should consider paying a little more for ASTM-rated #15 felt, which actually weighs 15 pounds per square.

You can use standard roofing nails or cap washers (metal or plastic) to hold the felt paper in place until covered with siding. The cap washers are a good idea if the felt paper will be exposed for more than a few days and may be subjected to windy weather that could tear the paper through the nails.

Best of luck with your project!

John B. says

I live in Houston and have a stucco home with attached garage. Following flooding from Hurricane Harvey, I removed the bottom two feet of slightly moisture damaged drywall and R-13 insulation throughout. I noticed behind both a horizontally installed black plastic wrap. I am unsure whether this wrap is PPE, PE, or something else. This material was installed only on exterior walls. The wrap is believed to be original construction dating to when the house was built in 2000. To provide a visual, if you were observing this wrapped area from the garage interior, the plastic wrap measures approximately 8 inches bottom to top, was horizontally installed, crossing the entire bottom layer (cavity and stud) of the wall. The wrap is installed against a plywood layer and sandwiched between the R13 insulation and the studs. Would this wrap possibly be a moisture barrier? If so, I would like to upgrade the barrier, as it was slightly torn during the drywall removal, however I would like to do so without removing it. Having read your article, I am considering whether it would be prudent to install a single layer of felt over the torn plastic wrap. This would serve to patch the torn plastic wrap area while also serving as to upgrade the moisture barrier. Would doing so be in any way harmful or provide the benefit I am looking for? If beneficial, I would like to install additional felt over the plywood and between the studs, covering the remaining 16 inches of exposed cavity. I am planning to install new insulation and drywall over this exposed area by October end. Thanks!

buildingadvisor says

Sorry to hear you were flooded by Harvey and hope your home didn’t sustain too much damage.

It’s difficult, from your description, to tell exactly what type of wall system you have. For example, what type of insulation do you have and is it between the studs or on the exterior side of the wall? Also, what type of moisture barrier is directly under the stucco?

The most common underlayment for stucco is two layers of Grade D building paper. However, one- or two-layer synthetic materials are sometimes used instead of Grade D. If you wish to send a photo or drawing, I may be able to provide additional info.

Most likely, the 8-inch-wide plastic sheeting you see at the bottom of the wall is an extra layer of protection behind the weep screed. The weep screed is a metal flashing at the bottom of a stucco wall with perforations to allow any accumulated water to drain out of the wall system. Stucco is not considered a water-tight wall system, so the wall must be designed to drain water. The illustration below, from the EPA report: “Flashing at Bottom of Exterior Walls” shows a typical detail for stucco over wood framing.

In a stucco wall, the drainage plane directs water to a weep screed at the bottom. Metal or membrane flashing behind the weep screed protects the wood framing from water damage. Source: “Flashing at Bottom of Exterior Walls,” U.S. DOE EERE

___________________________________________

When the weep screed is attached to a wood-based sheathing material such as plywood or OSB, then a second flashing must protect the sheathing from the weep screed. This can be a wide metal flashing, self-adhesive flashing membrane, or any durable material that will safely drain the water and protect the wood framing.

If this sounds like you’re your wall system, then you may need to remove and replace a section of this flashing. Peel-and-stick flashing membrane is probably your best bet for repairs. It is highly durable and sticks aggressively to most materials – including itself if you are not careful when installing.

Daniel Kauffman says

Why must the plywood or sheathing be protected from the weep screed? Is it because the metal should not direct contact with the wood? Like dissimilar material separation?

buildingadvisor says

Weep holes along the base of the wall are part of the drainage system required with porous cladding materials such as stucco and brick or stone veneer. With stucco, the weep screed allows water to safely exit at the bottom of the wall without reaching any wood components. The best stucco systems are designed with an intentional drainage gap between the cladding and the wall, which is covered with a water-resistant barrier (WRB). With stucco, the gap can be created with metal furring or a plastic drainage mat, allowing free drainage of any water that penetrates the exterior.

Luke says

Best Underlayment for Stucco?

Very thorough explanation. Thank you. It seems like you have a preference for felt paper over brown paper or Tyvek and other plastic housewraps. What would you recommend for stucco on an older open frame house in which the siding was removed and stucco will be the replacement?

buildingadvisor says

The standard underlayment for stucco in the US, and the code requirement in many areas, is two layers of Grade D building paper or asphalt-felt. Grade D is a reinforced, asphalt-impregnated paper similar to the backing on fiberglass batts. It is thinner than asphalt felt and easier to work with, but more vulnerable to water damage.

Plastic housewraps have been tried to some extent with stucco, but the results have been very mixed and they may not be accepted by code for this use. Plastic housewraps tend to deteriorate when in direct contact with stucco. If you wish to use a housewrap such a Typar or Tyvek, you can use it as the inner layer (if permitted by code) covered with an outer layer of Grade D or asphalt felt. Attach the expanded metal lath with special lath nails, which leave a small capillary gap between the stucco and the building paper. Lath nails also produce less water leakage than the commonly used staples.

If you live in a wet climate and want to upgrade from Grade D paper, I would recommend adding a drainage layer on the exterior of the underlayment. Plastic drainage mats made for this application include MTI Sure Cavity and Stuc-O-Flex Waterway-Rainscreen.

Fortifiber offers a few options, which have been accepted by code as a stucco underlayment in many areas. Fortifiber’s Two-Ply Super Jumbo Tex 60 Minutes combines a water-resitive barrier with a drainage layer, making it is a good choice for a wet climate. They also offer a single-layer version laminated to a drainage layer, called HydroTex, which they recommended for “wet and windy” conditions.

Read more about Rain-Screen Walls