Q: Do heat pumps work in cold weather? I have a leaky farmhouse in Vermont with an old oil furnace. One contractor recommended adding a couple of mini-split heat pumps in the main living spaces and to use the oil furnace as a backup when it’s below zero. How much can I expect to save on my heating bills? — Gary M.

A: Until recently, heat pumps were mainly used in mild climates where central air-conditioning was needed along with a modest amount of heating. Heat pumps can provide both efficient heating and cooling. On the heating side, heat pumps can cut the costs of electric-resistance heating by 60% or more, as long as it does not get too cold for the heat pump to operate efficiently.

Because of the high cost of electricity in many areas, heat pumps are usually more expensive to operate in winter than a gas furnace. Compared to oil or propane heat, however, heat pumps are almost always less expensive to operate, unless electric rates are very high – more on this below.

Traditional heat pumps were moderately efficient at heating as long as it was above freezing. The higher the outdoor temperature, the more efficient the heat pump and the more heat it can produce. So, for example, a heat pump that delivers 50,000 Btu/hr at 50 °F might product only 40,000 Btu/hr at 35°F.

Also the efficiency drops as the temperature drops. Below 20 to 30°F, most traditional heat pumps rely entirely on electric-resistance heating elements inside the unit, so heating costs more than double during cold spells. The cost, at these times, is the same as electric resistance baseboard.

Newer cold-climate heat pumps have largely solved the problem of extracting heat from very cold air, allowing them to operate economically down to 5°F or below. They have done this through more efficient compressor design and control strategies that use multiple stages or variable speeds.

What is a Heat Pump?

A heat pump is, essentially, an air-conditioning system that can run in reverse for heating. It doesn’t make heat like gas or electric furnace, but just moves it from place to place.]

In the cooling mode a heat pump removes heat from inside your house and transfers it to the outdoors. In the heating mode, it removes heat from the outside air, and moves it into your home. You could make a crude and inefficient heat pump by taking your window air conditioner and turning it around in cool weather so it blows the hot air inside and the cold air outside.

To transfer the heat, a heat pump uses a fluid refrigerant with a low boiling point such as Freon. Heat pumps follow the same “refrigeration cycle” used in air conditioners and refrigerators. This takes advantage of the fact that a liquid absorbs a lot of heat when it evaporates into a gas and gives up a lot of heat when it condenses back into a liquid. A compressor is used to force the gas back into a liquid and keep the cycle going.

In heating mode, cold liquid refrigerant absorbs heat from the outdoors as it passes through the outside (evaporator) coil, turning into a gas. The gas heats up when it passes through the compressor. The hot, compressed gas then flows indoors where it gives up its heat as it condenses back to a liquid in the inside (condenser) coil. A fan in the air handler blows air through the condenser coil to distribute the heat to the house. The liquid refrigerant then passes through an expansion value that reduces its pressure, dropping its temperature. The cold liquid flows to the outside unit to repeat the cycle.

As long as the refrigerant is colder than the outside temperature, it picks up heat, driving the heating cycle.This works because the boiling point of the commonly used R22 refrigerant is -40°F. As the gas is compressed, it heats up to as much as 150°F to transfer the heat indoors.

In cooling mode, the fluid direction is reversed with the inside coil functioning as the condenser and the outside coil acting as the evaporator.

Cold-Climate Heat Pumps

Heat pumps designed for use in cold climates are fairly new in the US and just started to catch on in the mid 2010s. They have gotten a boost from state energy offices and utilities promoting heat pumps as a cost saving alternative to fossil fuels. Also, like electric cars, they are promoted as a clean energy source since electric production has the potential to produce less air pollution and greenhouse gases than fossil fuels. They are especially cost effective in areas with low electric rates and areas not served by natural gas.

Most cold-climate systems are suitable for areas with a design temperature of about 5°F. The design temperature is what heating contractors use to size a system – so it can fully meet the heating load on all but the coldest days or the year – at least 97.5% of the time. The most advanced systems can still provide some heating efficiency at temperatures as cold as -20°F.

Cold-Climate Heat Pump Efficiency

The efficiency of a heat pump is measure by the COP (coefficient of performance). A heat pump with a COP of 3 produces three times as much heat as an electric strip heater for the same cost. A more useful measure is the HSPF (heating season performance factor) essentially an average COP for the entire heating season. Divide that number by HSPF by 3.4 to get the average seasonal COP. Remember that all these numbers are just estimates, like EPA mileage ratings.

So how efficient are these units? The most efficient are “mini-splits” produced by Japanese and South Korean manufacturers such as Mitsubishi, Daikon, and Fujitsu. Some of these have a seasonal COP as high as 3.8 and a COP at 5°F ranging from 2 to 3. Some of the Mitsubishi unis maintain a COP of 1.8 down to -18°F.

Most mini-split systems have no ductwork, which would lower their efficiency. The highest-efficiency mini-splits have outputs as high as 28,000 But/hr at 47°F and 20,000 Btu/hr at 5°F. The larger units tend to be less efficient. Also ducted mini-splits, designed for use with limited ductwork, have slightly lower COPs because of the energy lost distributing the air.

Many of the larger cold-climate heat pumps, designed for standard duct systems, have much higher capacity and some have seasonal COPs of 3 or higher. The best have COPs at 5°F ranging from 1.75 to 2.5, still very respectable for pulling heat from pretty frigid air. The largest of these systems can produce over 60,000 Btu/hr at 47°F and over 55,000 Btu/hr at 5°F.

This performance data is pulled from the database of cold-climate heat pumps compiled by NEEP (Northeast Energy Efficiency Partnership). It is sometimes difficult to get good apples-to-apples performance data from heat pump manufacturers, so this is a great place to start your search for equipment.

Best Uses of Mini-Splits

Ductless mini-splits function as space heaters, ideal for a large room or a small energy-efficient small house with an open plan. Or they can provide supplemental heat to an addition or hard-to-heat space in a larger home.

Some builders are successfully heating small superinsulated houses with a single mini-split and larger superinsulated homes with two ductless mini-splits, which can be installed for about the same price as a typical gas furnace. The key is to build a very tight and well-insulated shell with a fairly open plan.

Another option to consider is ducted mini-splits, which distribute air through limited ductwork to nearby rooms. These are designed for short duct runs with few elbows or turns. So, for example, they might work well for three small, adjacent bedrooms, adding design flexibility with only a minor loss of efficiency.

However, mini-splits are not suitable for large, spread-out houses. They do not have large enough blowers to work with traditional U.S. ductwork systems. They require heat pumps with larger blowers designed for traditional ductwork systems.

How About for Larger, Leakier Homes?

Larger cold-weather heat pumps suitable for traditional U.S. ductwork are available from most U.S. heat-pump manufacturers. The best can deliver up to 55,000 Btu/hr at 5°F, but most have COP of under 2 at 5°F and a season COP of under 3. These systems are useful in areas with design temperatures of about 5°F, but will probably be reverting to expensive resistance heating below 0. In areas with high electrical costs, these systems might not be cost effective unless another type of supplemental heat was available for the extra cold nights.

In new construction with a tight and well-insulated shell, this might be a suitable strategy in areas with a design temperature down to about 5°F. In retrofits, first weatherize and insulate the shell as best you can. Then with an accurate measurement of house tightness and a detailed heat-loss calculation, you can decide whether heat pumps are a viable option. If natural gas is not available, this may be your most cost-effective system.

How Much Money Can I Save?

The potential savings from cold weather heat pumps depends on the efficiency of the system, the cost of electricity and the cost of the competing fuels.

All cold-weather heat pumps are cheaper to operate than electric strip heaters. In general you will cut your heating costs by at least 60%. That assumes a HSPF of 8.5 (equivalent to a seasonal COP of 2.5).

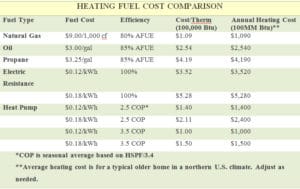

The more expensive your other fuel option, the greater your savings. Propane is usually the most expensive, followed by oil. Natural gas usually the cheapest and will cost less to operate than a heat pump. The efficiency of your heating equipment comes into play as do the shifting costs of fuel from one year to the next. Here are some average numbers (from 2019) to help put it in perspective. The house heating load of 100MBtus is for an average, large home in a cold climate.

Average electric rates in the US are about $0.12/kWh, but in the Northeast average rates are closer to $0.18. The higher the electric rate, the more it makes sense to invest in higher efficiency heat pumps. In most areas it is difficult to compete with natural gas under any conditions. With the highest-efficiency units and low electric rates, however, heat pumps and gas are running neck and neck.

How About Combining Systems?

In every case, the most cost-effective first step is to reduce your heating load as much as possible by building a tight and well-insulated shell in new construction. In retrofits, start with a good energy audit and do smart house tightening with the help of a blower door to pinpoint leakage points and measure the effectiveness of your weatherization efforts. Just guessing at where the air is leaking is rarely very effective as it’s often not obvious, even to experienced contractors.

Once you’ve reduced the heating load as much as you can without breaking the bank, take a look at your heating options. If you are also planning to install central air-conditioning, one or more cold-weather heat pumps is worth considering, even where natural gas is available.

In situations where you can’t meet the house’s entire heating load with heat pumps, you need to consider what your backup heating needs will be and how best to meet them. As mentioned earlier, electric resistance heating is the most common back up with heat pumps. The coils are usually inside the duct work of traditional ducted systems. With mini-splits, the back-up is more likely basic electric baseboard.

For modest usage on just a few frigid nights of the year, the high cost of running electric strip heaters might be easy to absorb. For situations with higher heating loads, and no natural gas, you will need to look at the cost of competing systems and available fuels. You might consider heating the most highly used portions of the house with efficient heat pumps and using the more expensive option, like a propane space heater, for a less used space like a home workshop or rec room.

Heat pumps are also a consideration for an addition where it would be expensive or impossible to heat with the existing system. In that case, the heat pump becomes the auxiliary system.

Are Heat Pumps Right For You?

New England is the only part of the US where hydronic (water based) heating system are the norm, so New Englanders may need to adjust to hot-air heating systems.

In other parts of the country, where hot air is the norm, there are still small adjustments.

Heat pumps do not deliver the blast of hot air that you may be used to with conventional gas or oil furnaces. The air temperature is lower, leading some people to complain of drafts. With lower temperatures, the recovery time is slower as well, so deep setbacks overnight can be a problem unless you have the system kick on well before you get out of bed.

Where heating is more dominant than cooing, you will want the inside units placed at or near the floor level – not ideal for cooling. Also think about the location of the outside unit. It needs to be protected from snow and ice buildup by raising it off the ground and protecting it from above by a sloped roof.

For people accustomed to silent hydronic heating systems, they will have to get used to the fan noise of a heat pump. For the very noise sensitive, even the sound of the outdoor compressor could be an issue.

As with any air system, filters need to be cleaned and replaced from time to time to maintain good performance.

Otherwise these systems require less maintenance than gas or oil burners and should provide years of hassle-free service. If you have a traditional ducted system, you may need to have the ducts cleaned every 5 years of so to keep the air fresh and free of mold – as with any ducted HVAC system. — Steven Bliss, Editor, BuildingAdvisor.com

Paul Beier says

Quantitative Data On Heat Pump Performance?

In my first half hour of searching for information on replacing my 30-year old gas furnace in an area (Flagstaff AZ) with cold winters, this site had by far the most quantitative and well explained information. Thank you.

Bee says

Hello i noticed the comment toward the end” Some builders are successfully heating small superinsulated houses with a single mini-split and larger superinsulated homes with two ductless mini-splits, which can be installed for about the same price as a typical gas furnace. The key is to build a very tight and well-insulated shell with a fairly open plan.” So is this meaning the mini split is being used as primary source of heat in thus structure? Are you in canada? The rule here is mini splits cannot be used as primary heat source, even if your house is tiny at 840sqft with minimum water pipes, to kitchen sink and a bathroom. Insurance companies are really giving homeowners a difficult time even cancelling home insurance with long term loyal customers because of this. I think it needs to be readdressed and given a minimum sq footage guidline for such heating units.

buildingadvisor says

We are based in the northern US, where it is a little warmer than Canada. Cold-climate heat pumps are being promoted heavily here by some utilities. The ductless systems top out at about 20,000 Btu/hr for one unit at 5 degrees F. The larger systems I have seen top out at about 50,000 Btu/hr at 5 degrees 5. At higher temperatures, the output and efficiency are higher.

As with any heating system, you need to match the unit with the heating load. With this type of heating system, your heating contractor will need to do a very precise heat-load calculation for your house — not a room-count or square footage rule of thumb. The key, of course, is to get the heating load low enough to make use of this type of system. That takes a builder with experience building low-energy homes. Getting the building code to approve of the technology is another issue.