Q: What are the best practices for a vented crawlspace? I bought a townhome last Nov. that has a vented crawlspace with a sump pump. There is a vapor barrier on the ground. There is a truss floor system that has faced batts that hang below the subfloor (the facing does not touch the subfloor), the rim joist was sealed with spray foam at the top and bottom and filled with batt insulation and then 2 in. of extruded foam board.

The foam board is not completely sealed (like it was tacked in with foam), and was only used on the two sides of the house that are exterior walls. The rim joists at the common walls with the neighbors are sealed with spray foam top and bottom and loosely filled with the batts – the ends of the batts in the truss area.

I live in WV where winters are cold and summers are hot and humid. Is my crawlspace insulated properly? Still, with all this insulation, the floors are cold, Can bubble foil be added to the bottom of the trusses to seal the truss system from the crawl space to prevent transfer of cold and heat? – J.M.

A: You’ve asked about what are the best practices for a vented crawlspace?

Crawlspaces are a regional building practice, popular mainly in the Southeast and the West Coast. They are less expensive to produce than a full basement and useful where a high water table would make a full basement impractical.

Vented crawlspaces work pretty well in the Western states, which tend to have dry conditions in summer. Unfortunately, crawlspaces have not worked out so well in the Southeast, especially as houses have become tighter and better insulated.

As you well know, there are a lot of wet, musty, and moldy crawlspaces in the Southeast and other regions with hot, humid summers. The most common, and cheapest, crawlspace insulation is fiberglass batts, which tend to collect moisture and provide housing for mice and other critters.

Because of the limited access, poor lighting, and debris that tends to collect, crawlspace problems are often ignored until the moisture problems are severe enough to be noticed in the living space.

Exterior Drainage

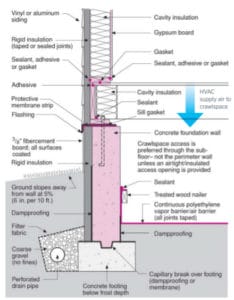

No matter with approach you use in a crawlspace, it is critical to reduce the moisture load introduced to the space. This starts with grading around the foundation, which should slope away from the building at a minimum of ½ in. per foot. This carries water from rain and snow melt away from the building. If it’s not possible to slope the soil away from the building, you can have a landscaper create a subsurface drainage system.

It is also important to direct gutter downspouts away from the house. You can use gravel trenches, drainage piping if needed to direct the water to daylight or a drywell at least 10 ft. away.

Ideally the finished grade inside the crawlspace is above the outside grade, but this is not always practical. If the outside grade is higher, use dampproofing on the exterior of the foundation walls and consider drainage board or waterproofing if wet conditions are expected.

Interior Drainage

Once you add a well-sealed ground cover, described below, or a slab, you have created a potential swimming pool in your crawlspace if you have a foundation leak or plumbing leak. If you are on a sloped site, where you can drain the foundation to daylight, a passive drain should work fine. In well-drained soil, a drywell is an alternative.

Set the drain in the lowest area of the floor, and run rigid Schedule 40 pipe to daylight or a drywell. Don’t forget to install a check valve to keep our critters. A check valve is also necessary in towns that require the outlet to plumbed to a sewer drain..

Where passive drainage is not feasible, or a seasonal high water table may try to turn your crawl space into a pool, by all means install a sump pump. It’s cheap insurance.

Ground Cover

No matter what approach you use in a crawlspace, vented or non-vented, it is critical to cover the ground with a durable moisture barrier. Even ground that appears dry can generate a lot of water vapor by evaporation through the soil. The ground cover has to be strong enough to withstand tradespeople and homeowners walking and crawling over it.

Thick (15-20-mil) plastic such as StegoWrap or reinforced polyethylene like Tu-Tuf work well, as do pool covers and proprietary crawlspace covers. Seams should be sealed with heavy-duty contractor’s tape or mastic.

Around the perimeter, the ground cover should to be turned up the foundation wall at least as high as the outside grade plus 6 in. and sealed with sealant and wood battens fastened to the masonry. Some contractors run the ground cover all the way to the top of wall for extra protection, leaving 6-12 in.at the top for termite inspection.

The ground cover needs to be cut and carefully sealed around any posts, piers, or other interruptions in the floor surface.

If frequent access is anticipated, or if you plan to use the space for storage, consider pouring a thin slab of concrete or “rat slab” of 2-3 in. thick to protect the moisture barrier and provide a walking surface.

A well-sealed ground cover goes a long way toward controlling moisture levels, but it is often not enough to prevent problems in hot, humid climates.

Unvented Crawlspace Better for Humid Climates

A lot of research has been done to determine the causes and cures for damp crawlspaces.

The consensus is that a vented crawlspace is not a good building detail for parts of the country with hot, humid weather. The traditional approach was to ventilate the crawlspace in summer and closed the vents in winter (for those who remembered).

However, bringing hot, humid air into a cool, damp crawlspace in summer is self-defeating. It just adds more moisture to the air and condenses on cool surfaces such as the crawlspace floor and masonry walls.

The problem is this: Warm air holds a lot more moisture than cool air. So the ventilation is actually adding moisture to the crawlspace. Furthermore, the cool surfaces in the crawlspace are often below the “dewpoint” of the outside air. The dewpoint is the temperature at which water vapor (a gas) in the air condenses into liquid water — like the beads of water that appear on the surface of a cold beer can on a hot summer day.

The water soaks into the insulation, floor framing, and subflooring. With the warm summer temperatures, these wet building components become a breeding ground for mold and, in extreme cases, wood decay.

Seal Space & Insulate Walls

So in areas with hot, humid weather, the best practice is to seal up the crawlspace and insulate the walls instead of the floor. In this approach, the crawlspace becomes part of the conditioned space of the home. Think of it as a basement with very limited headroom.

The building code in most areas call for R-15 to R-19 on crawlspace walls. Use foam board or closed-cell spray foam for the best performance and make sure the band joists are insulated and sealed as well. West Virginia is half in Climate Zone 5 (eastern) and half in Climate Zone 4 (western), with different insulation requirements. Check with your local building department.

Most people insulate crawlspace walls on the interior, although exterior foam is an option. On the interior, foil-faced foam does not need a fire barrier under most local codes, but other types of foam often need to be covered.

Add Exhaust Vent or HVAC Supply

Once you’ve sealed and insulated the walls, and covered the ground with a durable vapor barrier, the building code (IRC) requires that you either ventilate the crawlspace to the outdoors or heat and cool it with your hvac system.

The simplest, and probably most cost-effective solution is to add a supply duct to your crawlspace sized at 1 cfm per 50 sq. ft. of crawlspace. This makes the crawlspace into conditioned space. It seems counterintuitive, but research has shown that a house with a conditioned crawlspace uses less energy than one with a vented crawl space. And it should cure your cold feet as well.

An alternative approach is to install a small continuous exhaust fan sized to 1 cfm per 50 ft. of crawl space floor. Then add a floor register between the first floor and the crawlspace to insure that the return air comes from the house above, not the soil below. If you use a quiet, efficient fan, like the ones used for radon systems, you should get many years of quiet, maintenance-free service.

While you’re down there, add a few lights to the ceiling of the crawlspace. It will help you inspect the space when needed and encourage people not to use the space a dumping ground.

If You Don’t Want to Vent

If you’re on a nice high and dry building site, with excellent drainage, your crawlspace may be OK, even in a humid climate. If your crawlspace is free of moisture problems, and you don’t want to seal it up as described above, then I would recommend insulating the floor and band joists with closed-cell spray foam, or strips of foam board cut and fit between the joists – taped at the seams and sealed at the perimeter with spray foam.

It sounds like your builder did a good job of sealing the band joists against air leakage. Another leakage point is the joint between the sill and foundation wall. If a sill sealer was not used, the the joint should be sealed with spray foam or a high quality sealant such as urethane.

Don’t bother with the bubble wrap. Foil-faced bubble wrap is not a cost-effective insulation and will provide little extra savings or warmth.

As mentioned above, this approach works best in dry climates. In any climate, however, a crawlspace need an occasional inspection. You will want to check that the drains are clear, that no critters have moved in, and that the insulation is dray and the floor structure free of mold and wood decay.

Most codes call for R-19 (Zone 4) or R-30 (Zone 5) floor insulation. That’s a lot of foam, so you could consider installing just an inch of foam board or spray foam directly to the underside of the subfloor floor, and below it install a layer of unfaced fiberglass or mineral wool batts.

Or install the batts first and attach the foam board to the underside of the floor joist – with all seams taped and all perimeter joints and penetrations sealed airtight with spray foam. If your current fiberglass batts are dry in the summer and free of mold and critters, then floor insulation might be a viable option. – Steven Bliss, BuildingAdvisor.com

Read more on unvented crawlspace performance in this research report by the Building America Program (US DOE).

Elaine says

How To Seal Vapor Barrier to Crawlspace Walls?

We want to install a vapor barrier and seal to piers and perimeters. All the contractors we spoke with want to tape it to the perimeter skirting. I read that a long-lasting caulk or mastic is better. Do you think tape will stay on for decades or should we hold out for caulking?

buildingadvisor says

Not sure what type of tape they are suggesting or what the “skirting” material is they are bonding the poly to.

If they are sticking the poly to concrete walls, the most tried-and-true material, widely used in Canada, is acoustical sealant, which never hardens. However, the black, sticky goo is messy to work with, expensive, gives off fumes, which you may not want in a conditioned (heated/cooled) crawl space.

Next best would be butyl sealant. Some people have had good luck with duct mastic as well. Some polyurethane sealants work, but you really need to test beforehand.

With any of these sealants, it’s always a good idea to wire brush any dust and dirt from the wall where you are attaching the poly and to mechanically fasten the poly to the wall. This can be done with hammer-on plastic foundation pins or a pressure-treated 1×4 held in place with Tapcons or concrete anchor nails.

The only tape I would consider using would be double-faced butyl tape, sometimes sold as “crawl space tape”. Quality varies with different manufacturers. Again surface preparation is important and a secondary mechanical connection is always a good idea for long-term performance.

If you are fastening to a different skirting material, then a high-quality tape such as 3M Construction Seaming Tape might be fine. For an upgrade, consider Siga Rissan, an aggressive, high-performance tape which will probably outlast all of us.