See also Fine-Tuning a Floor Plan Building Plans & Specs

House designers usually focus on spaces when they create a design. They decide what spaces are needed, size and arrange them, then polish up the results.

In my own work, I try to think about how spaces are connected and how people move through the house. These connecting elements are known as “circulation.” Circulation elements include halls and galleries, and the parts of rooms people move around in.

Two Kinds of Circulation Space

There are two types of circulation space: “internal” and “public.” Internal circulation space serves the room or space it is in, while public circulation serves other spaces in the home.

Look at the plan of the renovated living room (Illustration above, at left). The internal circulation space has been darkened, while the public circulation space is shown in a lighter shade.

Notice how the public circulation gets you to your destination — in this case, the living room. Once there, you can either sit and talk or move around using the internal circulation. Consider the nice balance between rest and movement in the room. You are not compelled to move, but if you choose to, it is easy and convenient. In order to relax in a space, you need this balance between rest and movement.

Although the public circulation area is part of the living room, it is not defined by walls. The space must be there, however — a fact you can easily prove by blocking this route with furniture.

Now look at the drawing of the same living room before renovation (Illustration above, at right). Notice the clearly defined public circulation path running diagonally through the living room. See how the public corridor through the room upsets the balance between movement and rest.

It’s tempting to think of public and internal circulation as just abstract concepts. But imagine that you are sitting in the original living room talking to someone on the opposite side of the room. A person walks between the two of you, interrupting your conversation, if only for a moment. On the other hand, a person using the public circulation route at the other end of the renovated living room will have minimal impact on your private conversation.

The Central Hall

Public circulation also occurs in the separate spaces we call halls, corridors, galleries, entries, and passages. It is nearly impossible to draw a floor plan that lacks all of these separate public circulation spaces, but some plans make more use of hallways than others.

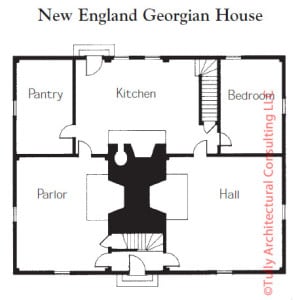

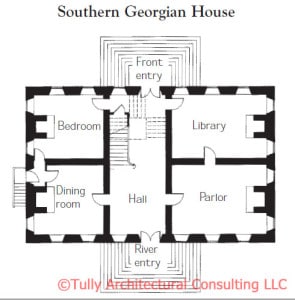

Look at the two plans of contemporary 18th century houses, one in New England and the other in Virginia.

In the New England house (Illustration, top), the separate circulation spaces are kept to a minimum and consist entirely of a tiny entry and the stairway linked to the upstairs hall. In this plan, most of the public circulation takes place within the rooms, linked only by doorways. By contrast, the most important space in the southern house (illustration, bottom) is the central hall, which contains a monumental staircase, connecting each room in the house. While it is possible to move between adjacent rooms by passing through a door, there is always another route through the central hall.

These two houses exemplify two distinct circulation patterns, which I call the “central hall” plan and the “linked rooms” plan.

Look again at the New England house, a classic linked-room plan. Because the back kitchen does not open off the front hall, the two front rooms have public circulation through them. This creates a loop of public circulation through the entire downstairs. This plan works fine as long as each room is large enough to accommodate the circulation space. There should be room for both a seating group around the fireplace and a public passage outside the group. This public circulation must avoid the “cut through” type of plan shown in the first drawing.

How Does It Feel?

Circulation impacts more than simple traffic control. Consider how you feel when you move directly from room to room, versus moving through a central hall between rooms.

Moving directly from room to room through a door can feel abrupt. On one side of a door the family might be sitting around the fireplace; on the other side there might be music, an intimate conversation, or an argument. Passing through a door in a wall is something like moving offstage in one play and suddenly finding yourself onstage in another.

On the positive side, a linked-room plan implies an intimate, cooperative sort of life. Imagine the 18th century family seated at the big table in the kitchen. Mother is sewing, father is reading the Bible, the kids are studying. The focus is on staying put around the fire, being together.

Exit Stage Left

When you move from a room into a central hall, the experience of movement is very different, even though you pass through a doorway. You have more choices once you are in the hall. You can catch your breath between encounters, have a private conversation away from the others, reprimand the children, receive newcomers. The central hall plan makes coming and going easy and graceful, thus encouraging entering and leaving. It presents a classical vision of hospitality and independence.

Continuing the theater analogy, with the central hall plan you move offstage from the first room into a sort of “backstage,” where you can collect yourself before going onstage again in the next room.

Treelike Plans

The old houses in the above examples didn’t have the many specialized spaces we have come to expect in homes today. Homeowners want a laundry, mud room, storage closets, and utility rooms, separate from kitchens and baths. To accommodate these specialized spaces, another plan type has become common, one I call “treelike.”

The idea behind such a plan is to arrange the rooms or spaces like leaves along a system of branches. Unlike the other plan types, treelike circulation fosters a sharp separation between movement and rest. You can’t use the long narrow halls for much of anything except movement.

Few of today’s plans are of all one type or another. Often, the living spaces are arranged in a linked-room plan, to which is attached a “treelike” pattern.

In conclusion, the quickest way to spot a “good” plan is to study its circulation patterns. Focusing your attention on how people circulate in a house will make you a better planner, or at least help you give constructive criticism to your clients’ plans.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Gordon Tully is the principal of Tully Architectural Consulting in Norwalk, CT. Gordon has practiced, taught, and written about residential design for over 40 years. This article first appeared in The Journal of Light Construction.

Leave a Reply