See Also: Circulation Building Plans & Specs

The question “What makes a good floor plan?” turns out to be very hard to answer because many subjective and mysterious issues arise. Even so, there are rules you should consider when planning a house (which, like all rules, should be thoughtfully broken at times). While important, these rules only get you to first base. A really good plan reflects an attitude about living, materials, and space.

Important rules to consider (and break thoughtfully) include:

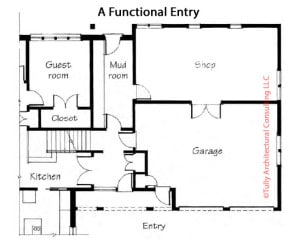

One entry should serve everyone. In most households, a separate formal entry is a holdover from the days of servants. People use the entry nearest the car, which usually means entering between the trash cans and cat box. Instead, create a nicely decorated entry, located near the garage and convenient to guest parking (see Illustration).

Guests enter through the front door, family through the garage — but all enter into the same handsome entry hall. Ideally, the mudroom, which holds all the paraphernalia of an entry — outdoor clothing, athletic equipment, muddy boots, etc. — should be a separate space adjacent to this entry hall. A further convenience is to open the back door and basement off the mudroom.

Gather in the light. Make sure light is available where and when it is needed. In the Northeast, where I practice, spirits sag during the frequent cloudy days. South light is essential in this climate, with east light a close second. West light needs to be controlled in all climates because of afternoon overheating in the summer. Arrange rooms so that the ones which really need the light are on the sunny side.

Pay attention to climate. Utility spaces and garages should be placed to shield the house from cold winter winds. In snowy climates, put garage and house entries on a sunny exposure to help melt snow. In many U.S. climates, an inside corner facing southeast provides outdoor space sheltered from cold northwest winds. Put windbreaks between the house and cold winds, and cut trees which block summer breezes and desirable sun.

Design the house into the grade. When the site is not flat, the house needs to respond to the grades. Sometimes bedrooms end up on the lower floor. The roof may cascade down the hill. A deck may project boldly into space. Don’t simply design a flat-site house and jam it into a sloping site.

Integrate the automobile. Most houses pretend the car isn’t there. The garage is glued onto the end of the house, with the front path and front door dead center, as if it were still 1760. A good plan responds to the actual way one arrives and leaves, usually by car. Even if the garage is hidden away below or to the side, the drive is the dominant element of the landscape, and no one ever uses the phony “front door.” Tie driveway, garage doors, and house entry together in a logical and handsome arrangement.

Doors should not interfere with each other. There are lots of ways to prevent doors from clashing, so there is no excuse for the problem, although some ingenuity is often called for. The illustration above shows several ideas.

Each room should be furnishable, preferably in more than one way. This will often require that windows be located in ways which appear informal and asymmetrical on the outside, but don’t let outside symmetry dictate how a room is furnished. In bedrooms, don’t force the user to walk around the bed in order to get to the closet or the dresser.

Don’t cut up rooms with through traffic. When you need to walk through one room to get to another, create a visual corridor on one side of the space, with an area of usable space next to the walking space. Don’t run the traffic diagonally through a room. Read more about CIRCULATION.

Try to open all the rooms off a common hallway. A room that can be reached only through another room limits the use of both. Open all the rooms off a common hallway, but then connect the rooms with each other (see Illustration). This creates a circular traffic pattern, which is very useful when cleaning or entertaining.

Don’t create a maze. This principle is hard to explain, and may seem somewhat subjective. Basically, when you have to walk around an obstacle, make it solid, rather than a meander of plaster walls. Typical solid obstacles are masonry walls, fireplaces, closets, bookcases, counters, changes of level, and staircases. Typical maze-creating elements are plaster walls, low space dividers, screens, and changes of floor materials.

Keep stairs open on one or more sides. Stairs jammed between walls feel uncomfortable and make furniture moving difficult. Leave one or more sides open, so the stair becomes a sculptural and space-forming element.

Create acoustically separate living areas. Especially in smaller houses, it is important for most homeowners to have more than one completely separated space for listening to music or television. Otherwise, anyone who wants to get away from the general hubbub must head for a bedroom or bathroom.

Create long views. Always try to line windows up on doorways as you enter a room, or arrange doors so that you can see a long way diagonally across a plan. This will help enlarge a small house.

Use the ceiling plane to create spatial extension. In small plans, it is often essential to break out of the pattern of continuous flat ceilings; this adds back the sense of spatial extension lost when the plan was condensed. Take advantage of breaks in the ceiling created by stairways and skylights. Drop the ceiling in strategic places, and use cathedral ceilings.

Avoid tunnel-like corridors. Widen a central hall or stair landing, and add bookcases and a place to sit. Bring light into a corridor from above so that it works as a gallery. Run the stair alongside a corridor to create a more complex space with vertical extension. When possible, run the hall on an outside wall and put in windows or glazed doors.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————— Gordon Tully is the principal of Tully Architectural Consulting in Norwalk, CT. Gordon has practiced, taught, and written about residential design for over 40 years. This article first appeared in The Journal of Light Construction.

sarah says

Modifying a HUD-code home

Do the federal codes for building manufactured homes allow for alterations of the floor plan or home?

buildingadvisor says

Is this a home that is already built or one that you are ordering from a manufacturer? In either case, any changes to the plan have to be in compliance with the HUD building code, which regulates basic structural and safety concerns as well as minimum size, size of bedrooms, number of windows, and other design issues.

If the home is already built and the modifications are extensive enough to require a building permit, then you will need to get a permit from your local building department. What exactly triggers the need for a building permit depends on local regulations. Your changes will also need to be in compliance with local codes although the federal HUD code takes priority if there is a conflict.

How familiar the local building department is with the HUD code varies a lot, but it is up to the local inspector to enforce the HUD code at this point. For example, HUD requires that anything added to the structure has to be independently supported and cannot put additional weight on the manufactured home.

For more information, contact your local department of building inspection or your local HUD field office at this link:

http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/program_offices/field_policy_mgt/localoffices