Q: What is the best way to insulate an unvented cathedral ceiling in a detached workshop? I plan to insulate before installing an AC and heating system (thinking mini-split). Is closed-cell spray foam the best, or only, good option in this case? I don’t plan on finishing the space with drywall, although wouldn’t rule it out in the future. .And given that it’s only a workshop with occasional use, I only want the minimum insulation (for cost reasons) to prevent moisture issues. I’ve living in Region 5 in Pennsylvania. Hoping you can advise. – Paul

A: Assuming you have full access to the joist spaces from below, you could certainly spray foam up against the roof sheathing. In general, closed-cell foam is the best choice for unvented cathedral ceilings. It provides a high R-value per inch as well as air and vapor control in one application, assuming it is done correctly. However, most building inspectors will not allow spray foam to be left uncovered (for fire-code reasons).

Spray foam is a very expensive option, however. Foam-board insulation would be a more economical, especially if you are supplying the labor (see photo). The foam board can be nailed to the bottom of the rafters, which is pretty straightforward, or cut into strips to fit in between the rafters — the so-called “cut-and-cobble” approach, which can be very labor intensive and difficult to do well.

Insulation and Moisture

In most cases, insulation will not help prevent moisture problems. In fact, insulation can lead to moisture issues if not done properly. The reason is this: In cold weather, insulation in the roof cavity makes the roof sheathing colder (the sheathing is insulated from the warmth below). The colder roof sheathing is then more likely to form condensation or frost on its underside if household moisture reaches the sheathing. Moisture problems are more common in roof spaces than walls due to the “stack effect” — warm, moist household air moving upward toward to roof in cold weather.

Moist indoor air could leak into the roof cavity through openings for ceiling lights, plumbing vents, wiring, or framing details that create gaps. With foam board, gaps in the insulation at joints and around the perimeter can also allow moist indoor air to reach the roof sheathing.

However, since this is just a workshop, most likely the indoor air will not have the high indoor moisture levels (from kitchens, bathrooms, houseplants, etc.) that can cause moisture problems. Other sources of high indoor moisture levels include storage of wet firewood, slabs without a sub-slab vapor barrier, or a very wet building site without proper surface drainage and subsurface moisture control.

Roof Leaks

The other problem with unvented, foam-filled roofs is that water from a roof leak can wet the sheathing and framing, causing wood decay, long before you see any evidence of a leak on the interior. Trapping water between closed-cell foam underneath and waterproof roofing above is a recipe for mold and wood decay.

Unvented spray-foam roofs dry out very slowly, and almost entirely to the interior, which is why you should never use an impermeable vapor barrier, such a poly sheeting, under the finish ceiling. If a vapor retarder is required by code, it is best to use one of the expensive “smart” vapor barriers such as MemBrain or Intello. With “cut-and-cobble” insulation, you will also want an air-tight “air barrier” such as well sealed drywall to keep household air out of the roof cavities. With properly installed spray foam, an additional air barrier is usually not needed.

Vented Roof Options

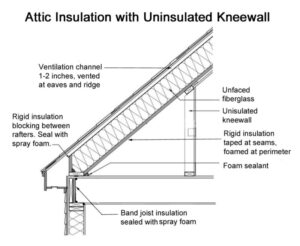

There are certainly other options. You could insulate the roof the traditional way. That is, create a vent channel above the insulation with low and high vents. Then insulate below with fiberglass or cellulose, add a vapor retarder and your finish ceiling. You’ll want an airtight ceiling air barrier, with no air leakage into the cathedral ceiling – a critical detail for all cathedral ceiling designs. You can add a layer of rigid insulation below the fiberglass and seal it with tape and canned foam to form an airtight air barrier (illustration below).

Research has shown that the amount of airflow in the vent channels of low-slope roofs is very limited for roofs with less than a 3/12 pitch. Also you must have adequate ventilation along both the lower and upper edge of the roof, and continuous venting channels in every rafter bay for effective ventilati0n. Even with limited airflow in the channels, wind and vapor diffusion also play a role in reducing moisture in the roof cavities.

If you really don’t want a finished ceiling below, but you do want some insulation, I would consider using foil-faced polyisocyanurate foam (iso-board) such as R-Max or Thermax. The easiest approach is to nail the form boards below the rafters (see photo above), and tape all the seams. Or to preserve headroom, you can cut strips of foamboard to fit between the rafters. In either case, carefully seal any gaps around the perimeter of the foam board with spray foam. Any gaps in the foamboard at seams or around the perimeter can result in condensation on the underside of the sheathing.

For this size job, you would want a large foam canister and professional spray applicator. Most codes allow foil-faced foam to be left exposed. Plus iso-board provides the highest R-value per inch for any type of insulation.

— Steve Bliss, BuildingAdvisor.com

Read more on cathedral ceilings:

Cathedral Ceilings, Combining Spray Foam & Fiber Insulation

Cathedral Ceilings, Hot-Humid Climates

Cathedral Ceilings, Insulating with Spray Foam

Cathedral Ceilings, Preventing Condensation

Cathedral Ceilings, Unvented, How to Seal

MM says

Can I Retrofit Radiant Barrier in Cathedral Ceiling?

Hi,

The bonus room on top of my garage gets very hot in the summer and stays warmer than the other rooms in the winter.

I want to add radiant barrier to my roof, but contractors have said that the ceiling is not accessible. I have pictures that were taken of the sloped roofs and there is fiberglass insulation against the ceiling, then baffles on the roof deck.

I have about an inch of space to slide a one inch foam board with radiant barrier facing up right over the fiberglass and under the baffle.

I was wondering if this would cause any moisture issues since the space is well ventilated and the radiant barrier would cause any moisture to not penetrate the fiberglass and would run down to the opening at the knee wall.

If this is not a good option, would installing a radiant barrier that is not foam but has perforations in it be a better option up against the baffle and over the fiberglass insulation? It would be more of a challenge since it is not rigid, but I can use a long pole with a grabber at the end to pull it through since the slope of the ceiling is about four feet to the top.

buildingadvisor says

You have about a one inch space between the top of the fiberglass insulation and the baffles, which you wish to fill with 1″ foam with a radiant facing up against the bottom of the baffles.

I’m also assuming that you would need to slide a long piece of foam insulation or radiant barrier up each joist bay. Is this correct. Please send any pics that might be helpful.

A couple of points:

• An inch of poly-iso insulation will give you an extra R-6 to R-7, which will help — although it will not be an airtight installation so the R-value will be somewhat compromised.

• Radiant barriers only work when they face into an air space of at least one inch. It’s best if the air space is ventilated. If the radiant barrier is tight up against the baffles, then it will not be very effective. Facing down against the fiberglass would also be ineffective.

If you install a radiant barrier up against the baffles, with a one inch airspace below, you will get some insulation benefit — about R-3 for the air space, depending on the emissivity of the radiant barrier, slope of the roof, and other factors. You will also get an additional benefit from the radiant barrier if the airspace above is vented. It is difficult to estimate the savings from the radiant barrier.

They are most effective when closest to the exterior of the roof — for example, the underside of the roof sheathing (facing a vented space) or below the vented space. In an attic with ceiling insulation, a radiant barrier can substantially reduce attic temperatures, which is particularly useful if air conditioning equipment or ductwork is located in the attic. In a cathedral ceiling like you describe, you might save 5 to 10% on cooling costs according to U.S. DOE. Again, this requires that the radiant barrier faces a minimum 1 inch air space. Many companies marketing radiant barriers make exaggerated claims.

Downward facing radiant barriers work better over the long run as they are less likely to collect dust and dirt, which will reduce the effectiveness. For example, using roof sheathing with a foil facing on the bottom side can be very cost effective (with a vented air space). In many cases, however, it is more cost-effective to add more insulation rather than a radiant barrier.

As for moisture problems, the key is an airtight air barrier on interior. If you are concerned about trapping moisture in the cathedral ceiling, then using a perforated radiant barrier could make sense. To be effective, a radiant barrier does not need to be airtight. It is reducing radiant heat flow downward, not stopping air and moisture flow upward.

Best of luck!

Steve

MM says

Thank you for getting back to me. Here are some photos that hopefully will make things more clear since the old adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” applies here:

Here’s the interior view of the bonus room over the garage with the knee walls up to 5 feet and then sloped ceilings and then flattens at the top (see pic below)

There is insulation behind the knee walls and we will be adding radiant barrier to them, but I would like to add radiant barrier to the ceiling slope and the flat part of the ceiling, but this is what they look like inside:

Flat part of ceiling over room (see pic below)

Top part of knee walls where sloped ceiling begins (see pic below)

The lighter color insulation on the bottom is the top part of the knee wall insulation. So you can see that there is only about 5 inches of space in the whole sloped ceiling part of the roof.

I am wanting to add a 1/2 inch firm radiant barrier foam board directly beneath the baffle shown that would create a 2 inch air space from the roof to the radiant barrier

Here is what the bonus room over the garage looks like from the exterior

The right side in the photo faces west and gets the hot sun in the afternoon. The room bakes in the summertime and we would like to cool off the room. It is the warmest room all year round including winter, but it’s like a sauna in the summer.

We will also be adding this firm foam to the roof deck the slopes in the attic space to either side of the knee walls.

I haven’t been able to try and see if I can slide the foam board up into that space yet since we don’t have planks laid down in that space and I am afraid of falling through and we will be having someone install them, but when they do, I hope to try and see if I can fit one inside of those tiny spaces.

I just want to make sure that it’s not going to cause any problems and that it would be worthwhile. I already put them on the inside of my garage door and have noticed a difference.

Now that you are able to see the photos, any words of wisdom you can share?

Thanks in advance.

Michele

buildingadvisor says

Photos submitted by MM

Thanks, Michelle, for the pics and added info.

As for words of wisdom….

It looks like the fiberglass insulation is tight against the ventilation baffles in the sloped section of the attic. So I don’t understand how you hope to get a radiant barrier in these areas. Even if you do, you need an airspace (minimum ¾ to 1 inch) for the foil to work its magic. It works better if this space is ventilated. Without an air space, the radiant barrier is pretty useless.

However, adding an inch of foam – if you can make the installation reasonably airtight, will provide additional R-value.

Adding a radiant barrier on the kneewalls and top section of the roof (above the flat ceiling) will help somewhat. The easiest and most effective place for a radiant barrier would be directly under the sheathing (shiny side down) – with gable-end vents or soffit and ridge vents. Or stapled across the bottom of the rafters (shiny side up) with soffit and ridge vents.

On advantage of shiny side down is that dust is less likely to accumulate on the shiny surface, degrading the radiant effect.

Hope that helps!

Steve

TC says

Should I Insulate Vented Cathedral Ceiling with Foam or Fiberglass?

I live in Denver and have a bedroom built into what was originally attic space, this has resulted in a 2×6 rafter cathedral ceiling that is currently un-insulated (but does have soffit/ridge venting). We are going to get the roof re-done and wanted to get insulation installed while that is happening. The contractor wants to install Foamular boards between the rafters leaving an airgap to the sheathing above. We have lots of places for interior air to move into the roof space via fixtures and poor sheetrock/trim work. Will Foamular between the rafters create pockets that trap humidity and potentially rot out the rafters? Would bat insulation be better since it can breath? Thank you,

buildingadvisor says

If you have adequate ventilation (soffit and ridge) above the insulation, then it doesn’t matter whether you use foam or fiber insulation.

To get good energy performance with either approach, however, you need to install the insulation well, without voids and gaps. When cutting foam board to fit between rafters, this is typically done by taping seams and foaming around the edges of the boards – a time-consuming operation. One advantage of foam is that you can pack more R-value in a smaller space.

To prevent moisture problems with either approach, you need to keep household air from getting into the rafter cavities. You cannot rely on the ventilation to prevent moisture problems. Roof ventilation is a backup system that allows some drying to take place if excess moisture builds up. The main strategy is prevent moisture problems is to keep moist household air out of the roof cavity.

This is done with a continuous “air barrier” on the warm side of the insulation. A good way to achieve this, and get extra insulation value, is to install a continuous layer of foam board across the bottom of the rafters. Tape all seams with high-quality construction tape suitable for the type of foam used. And foam around the perimeter of the foam board with canned spray foam. Pay attention to anyplace that vertical walls, pipes, chimneys, or other building elements intersect with or penetrate the ceiling. Any of these vertical channels can carry warm household or basement moist air into the cathedral ceiling.

You can read more on the topic at these links:

Cathedral Ceilings, Preventing Condensation

Attic Air Sealing & Insulation

Cathedral Ceilings, Unvented, How to Seal

Nancy Price says

Rigid Foam vs. Plywood for Ventilation Baffles?

Have cathedral ceiling. If I add a 1.5-2 inch blocks to the inside of roof rafters, can I use rigid foam board as a baffle? This would require taping foam boards and using spray foam to seam boards to rafters. This should give me sufficient airflow. Pre made baffles are thin & can be crushed by insulation plus warranty only a year. Looking for a better solution. Have read about using luan to form a baffle-like air space. . One shot to do this right. Have metal roof and may use metal for the interior ceiling?

buildingadvisor says

Yes, you can certainly use either thin plywood or rigid foam insulation for baffles. Either would be better than the thin plastic baffles that are often used. As you mention, many of these can be easily crushed or damaged.

Most lauan plywood, however, is made for interior use only, so might delaminate or degrade if it gets wet. You might want to use exterior grade lauan or 3/8-inch cdx plywood, which is rated for exterior use.

If you go with rigid foam, I would avoid foil-faced foam as it is completely impermeable to moisture. Also don’t tape the joints or foam the edges. With a vented cathedral ceiling, moisture in the insulated cavity should have a way to reach the ventilation channels, for effective drying. For that reason, I prefer baffles that are somewhat permeable to moisture.

Even more important is to have an airtight air barrier on the finished side of the ceiling. If you are using a metal ceiling, you will want to first install drywall, sealed at all seams and edges, or a “smart” vapor barrier (such as Membrain) that is carefully installed in an airtight fashion.

Keeping excess moisture out of the cathedral ceiling is the primary defense against moisture problems. Ventilation is intended as a back-up system only and cannot be relied on to prevent moisture problems in a cathedral ceiling.

Ben Dill says

Best Details for Cathedral Ceiling in Attic

I have an 1870s double layer brick farmhouse in Northeast Indiana. I am finishing the attic into a toy room. I have Styrofoam insulation baffles running from soffit to ridge, but the rafter spacing is variable from 14-20″ so the baffles don’t fill the entire width of the cavity.

The rafters are old true 2×6 and 2×8 rafters. The attic is T shaped, so the long leg is 2×8 rafters and the cross part is 2×6 rafters.

I want to be sure I insulate and finish the ceiling correctly to prevent moisture damage without sacrificing ceiling height. My research suggests the correct approach is to fill the cavities with unfaced insulation Batts, then install foam board insulation and seal the seams, then put in furring strips and attach the drywall to the furring strips. I’m resigning myself to the fact I need to do this, but don’t like the jdea of losing that much ceiling height (the peak is only 7’9″, and the attic is 20′ wide on the long leg and 15′ wide on the cross part.

Here are my questions.

1. Is it OK that the Styrofoam insulation baffles do not fill the full width of the cavities?

2. The ceiling extends all the way down to the attic floor, so I’m not sure how to seal the foam board at those edges.

3. Can I use 1×2 or 1×3 furring strips and screw the drywall directly to the furring strips?

4. The rafters are incredibly hard. Any suggestions for nailing foam board, furring strips and screwing drywall efficiently?

5. The attic access is a winding staircase so getting drywall to the attic in full sheets will be a challenge (as in impossible). Any recommendations on drywall alternatives?

buildingadvisor says

See answers below:

1) Is it OK that the Styrofoam insulation baffles do not fill the full width of the cavities?

Insulation baffles the full width (or nearly full-width) of the cavity are best, as you don’t want moist air to condense on the cold underside of the roof sheathing. Flimsy baffles that crush under pressure from the fiberglass should not be used. Also, the cavities need to be coupled with low and high roof vents to be effective. Remember that roof ventilation is only a back-up system. The most important thing is to keep moist household air out of the roof cavities by building a tight air barrier at the ceiling level.

2) The ceiling extends all the way down to the attic floor, so I’m not sure how to seal the foam board at those edges.

This is a tricky place to seal. Canned foam sealant is usually the best choice. I recommend buying a professional-grade dispensing gun such as this one. The exact method will depend on how the framing is detailed at the eaves and what type of access you have. The detail shown in the article above below works with or without a kneewall in the attic.

3) Can I use 1×2 or 1×3 furring strips and screw the drywall directly to the furring strips?

Yes, furring strips are the most common approach. Some people use long screws to fasten the drywall directly to the rafters, but this is tricky. Depending on the type and thickness of foam, you may get a wavy surface or you may get screw heads pulled though the drywall when the compressed foam re-expands (sort of a reverse nail pop).

4) The rafters are incredibly hard. Any suggestions for nailing foam board, furring strips and screwing drywall efficiently?

Well, a nail gun would be great if you had one – electric or pneumatic. If you are hand nailing and keep bending nails, you could try a hardened steel masonry nail. These are usually pretty chunky, so you would need to find a thinner type like this – a specialty item. Also you will want to use metal or plastic caps at each nail. You could also attach the furring with framing screws, which tend to be pretty hard. If all else fails, you may need to predrill pilot holes.

As for efficiency in screwing the drywall, unless you want to spend a lot of money on a collated screw gun, I’m not sure. Certainly a drywall driver bit helps speed things up and sets the screw heads just right.

5) The attic access is a winding staircase so getting drywall to the attic in full sheets will be a challenge (as in impossible). Any recommendations on drywall alternatives?

Sorry, but don’t have any suggestions. There used to be a product called rock lath, sold in 16×48-inch sheets and used for as a plaster base, but it’s no longer sold and would require an awful lot of taping and mudding. You can buy small drywall repair sheets, but these would have the same issues. Maybe cut each sheet lengthwise, if that would fit up the stairs. You may have better luck with 3/8-inch drywall, which is lighter and a little more flexible.

Pat says

How About Adding Foamboard Above Roof Sheathing?

Hi I have a mid century home with cathedral ceilings currently a hot roof it consists of exposed beams then thick tongue and groove 2 1/4” thick then 1” foam board followed by a sheet of plywood with asphalt shingles over that I need to re roof my house currently and want to increase the r value I was considering adding 2 layers of 2” polyiso foam then re roofing it I’m curious what the best practice would be on this roof if I should add a vapor barrier and then the foam with firing strips and vent it or just replace it as a warm roof

buildingadvisor says

Depending on the type of foam, you currently have R-4 to R-7 insulation in the ceiling, plus another R-4 for the 3 in. of wood. In most parts of the U.S., that is not enough to prevent condensation on the bottom of the foam in cold weather. See Table 1 in the article on flash-and-batt insulation in cathedral ceilings for recommended levels of insulation in unvented cathedral ceilings.

If your current hot roof is not experiencing any moisture problems, then I see no need to add ventilation below the additional foam. Adding more foam above the existing roof sheathing will improve the performance of your roof system by increasing the temperature on the bottom surface of the existing foam – reducing the likelihood of moisture problems.

Just make sure that the new foam is well-sealed at all seams with durable construction tape and sealed with canned foam around any openings or penetrations through the roof.

Assuming you have about R-20 with the 3 in. of foam in the completed roof, and about R-3 with the wood ceiling below the foam, the R-value at the bottom surface of the existing foam will be about 61° F when it is 68 indoors and 20 ° F outdoors. That’s well above the 45 °F minimum specified in the building code for the “plane of condensation” in most parts of the continental U.S.

The temperature gradient in a ceiling is proportional to the R-value above and below any point in the assembly. In this case, the R-3 accounts for 15% of the R-20 total. The temperature difference is 48 °F, so the temperature at the bottom of the foam is about 7 °F (15% x 48) colder than the indoor air. You can read more about this calculation at this link.

Bottom line, you should be good to go with addition foam and no ventilation channel!

Steve M says

How To Insulate Cabin Roof in Minnesota?

I’ve been reading much of the comments here on your site and find them very helpful regarding insulating a vaulted ceiling. My situation is rather unique in that the cabin is only occupied randomly through all 4 seasons here in Northern Minnesota.

I am rebuilding the roof and wondered about the proper sequence of layers of materials to complete the roof. Here is what I have in the order they are in place from top of roof to interior:

Metal roof, synthetic Felt roll membrane, Plywood, Foam sheets 5 1/2″ total (Pink), 1 1/2″ tongue and groove pine ,Rafters exposed to living space.

Any comments suggestions on what to improve or change here?

Thank you from northern Minnesota

buildingadvisor says

Assuming your pink insulation is extruded polystyrene (XPS) such as Foamular, you’ll have a nominal R-Value just above R-27. That’s not up to code in most places, but probably OK for a cabin that gets only occasional use.

Also, your moisture loading from bathing, cooking, houseplants, etc., should be pretty low as long as you don’t have a wet crawl space, drying firewood indoors, or other significant sources of indoor moisture.

To be safe you will still want to an airtight seal along all seams and edges of the interior surface of the foam to keep interior air out of the roof cavity where it can lead to moisture problems in an unvented roof like this.

For best performance, you should also seal each layer of foam around the perimeter of the roof with canned foam to limit air movement within the insulation .

You may want to consider placing the plywood directly against the rafters for the structural benefits.

Then you could attach 1×4 or 2×4 purlins on top of the insulation with long nails or long structural screws and attach the roofing raptor the purlins. That approach would provide a much stronger roof structure.

Nick says

Radiant Barrier in Cathedral Ceiling?

I have a very similar situation to Paul – I am also trying to decide how to insulate the cathedral ceiling in my attached workshop – but there are a couple minor details that I’d love some clarification on.

I live in S. AZ, so “Zone 2, hot & dry”. Does it make sense to apply a radiant barrier directly to the underside of my roof deck, then fill the rafter bays with 2-4 inches of rigid foam board (leaving a 3/4″ gap above the foam)? I would then tape & seal the foam. My reason for wanting to use rigid foam instead of fiberglass is that my rafters are only 2×8, so I’m trying to maximize R-value-per-inch.

Thanks!

Nick

buildingadvisor says

In a hot climate like yours, a radiant barrier can have a signficant effect on the cooling load. The minimum recommended air gap below the radiant barrier is ¾ inch. More is better, and a vented gap is more effective than an unvented gap as the hot air will naturally flow upward and out the ridge or high end of the roof.

It’s fine to use rigid foam between the rafters. It’s important that you create an airtight air barrier at the ceiling level. You can use the foam for the air barrier if you seal around the edges with canned foam and seal the seams with contractor’s sheathing tape or a similar durable tape suitable for the type of foam you are using.

If you use more than one layer of foam, you need to seal the bottom layer, but sealing both layers will give you the best performance.

Vic says

Where To Put Air Barrier In Vented Cathedral Ceiling?

I have a tiny building, 8×24 with a pretty steep pitched vented roof, I am re-insulating as my loose insulation compacted down to the eaves from the roof line.

A family member said to use 1 inch Foamular 250 as my vent channel, then put my paper-backed insulation which would provide the air seal once taped. I would then put up paneling or tongue-and-groove boards. Is this OK?

I read something about double vapor barriers. But if there isn’t spray foam sealing off the foam board. would that be OK because if moisture got in it could get out. Or do I need to seal it off? So paneling, kraft paper-backed insulation, foam board, vent space, then roof. Also, I have a metal roof so my place gets pretty hot, no shade.

buildingadvisor says

A vented channel under the sheathing of 1-1/2 to 2 inches will provide good ventilation as long as you have adequate vent strips or all along the low end and high end of the roof. Code calls for a min. 1 in. channel, but 2 in. works much better.

To create the baffles, you can use just about any durable material. Manufactured baffles, osb/plywood, or foam board are the most common. The main advantage of using foam board is that you get more R-value than using a non-insulating material. Also the foam board is relatively easy to cut, very durable, and easy to air-seal with spray foam. Using foil-faced foam board will provide a radiant barrier, which will help with your overheating problem.

If you have air-sealed the foam board to the rafter bays, you do not need any additional air sealing below the insulation. In a very cold climate a Class II or III vapor retarder, such a kraft paper or painted drywall is recommended on the interior side of the insulation. In a hot or temperate climate, its best to have no interior vapor retarder.

The most common place for the air barrier is below the insulation. The least expensive option is usually carefully taped drywall, sometimes with gaskets or sealants where needed. Taping Kraft paper well enough to create an airtight barrier sounds difficult to impossible. Poly sheeting is a poor choice as you don’t want a Class I vapor barrier in any ceiling – it does not allow any drying to the interior.

If you don’t want to use drywall, try this: Use inexpensive plastic or cardboard baffles under the sheathing with unfaced batts or blown-in insulation filling the rafter bays. Then nail your 1-inch foam board to the bottom of the rafters, tape the seams, and seal the perimeter. Then you’re ready to install the paneling (and have eliminated the thermal breaks at the rafters).

I don’t know your climate zone or the building use. If it has a high moisture load in a cold climate, your need to take extra precautions or the moisture may end up in your roof cavities. In a dry building (like a workshop) in a moderate problem, you’re unlikely to have moisture problems. In a hot, moist climate, you need to be concerned about moisture driven inward by solar energy. In a hot, arid climate, moisture is usually not a concern.

Vic says

Thank you for replying I appreciate any advice you can give.

It will be a tiny house with a kitchen and bathroom, that I will live in full-time.

Climate is Mediterranean I believe, not sure of the zone. In the last 8 years we have had summers up to 112 degrees F for a couple of weeks, we have lots of rain…like a lot of rain, winters have seen everything from a lot of rain to 19 inches of snow overnight to freezing rain for a week with -15F temps and loss of power frequently in the winter for minimum of 7 days. Eventually I will have a wood stove.

For the unfaced batts, would fiberglass or roxul mineral wool be better as I don’t want it to compress creating voids again.

buildingadvisor says

That’s a pretty extreme climate. Everything I wrote earlier still holds. Just a couple of other reminders:

1) The quality of the ceiling air barrier is much more important than the roof ventilation, which doesn’t always work as intended. If no moist air leaks into the roof structure, you won’t have problems with condensation under the roof. Of course, roofing and flashing leaks are always a concern and are much more likely to cause roof damage than air leaks from the interior.

2) In such a small house, keeping indoor humidity levels under control will be important. If you have water condensing and running down the interior side of insulated glass, then your indoor humidity levels are too high and could lead, over time, to damage to the structure. You can address this in two ways:

• limit the sources of moisture, such as house plants, drying firewood, humidifiers, wet basement, etc.

• Increase the level of indoor ventilation. Start with point-source ventilation such as bath fans and kitchen range hood. Then add whole-house ventilation if needed. This could be a heat-recovery ventilator (air-to-air heat exchanger) or a simple method of running one of your bath fans on a regular schedule using a timer.

Regarding the type of batts, either fiberglass or mineral wool would be fine. Settling is common with loose-fill insulation (fiberglass or cellulose), but is generally not a problem with batts. Maybe the voids you discovered were due to sloppy installation more than compression.

Keeping a full depth of roof insulation over the eaves requires special framing details unless the rafters are sufficiently deep. Some contractors raise the rafters where they attach to the top plate to make room for extra insulation over the plate. The traditional connection with a birdsmouth cut in the rafter at the top plate requires that the insulation be trimmed there to allow airflow from the soffits into the roof channels.

Using a layer of foam insulation on the underside of the rafters is a good way to provide adequate insulation at the eaves.

Tyler says

How Much Ventilation Needed for Cathedral Ceiling?

Hi,

Got a 16×20 two story shop that needs insulating. Live in zone 6 semi arid yet potentially prolong snow loads in winter. Concerned about how to insulate and air seal upstairs ceiling. I believe it’s a vented cathedral. The top has ridge center and at the moment there are no soffits just a solid board with gaps along the edges. One question is how many holes in each side to drill for soffit vents and the other is would the rigid foam board with foil on one side cut and spray foamed into the rafter spaces be okay with let’s say drywall on the rafters? The inside roof decking already had a radiant barrier type coating on it. Pitch is I believe 6/12 . There isn’t and won’t be plumbing just electrical. Thanks for your input!!

buildingadvisor says

It is difficult to get adequate ventilation for a cathedral ceiling with vent holes. Continuous vent strips are a better bet. It’s important to get ventilation into every rafter channel. The code requirement of a net free vent area (NFVA) equal to 1/300 of the attic floor does not really apply to cathedral ceilings. Researchers who have studied cathedral ceiling ventilation recommend 10-20 sq. in. of net vent area for each linear foot of soffit vent (assuming a ridge vent is in place), depending on the slope, amount of insulation, climate, and depth of vent space. They recommend a min. 1 1/2 in. air space under the sheathing for ventilation, 2 in. if possible.

FOr the radiant barrier to work, you need to make sure it faces a vent space. YOu can use any type of foam you want between or under the rafters. A layer under the rafters is the easiest to air seal (with tape and spray foam) and reduces thermal bridging through the rafters.

Experts debate the effectiveness of ventilation in cathedral ceilings, but it does help to some extent with ice dams, cooling loads, shingle longevity, and drying potential if the roof structure gets wet. But it has to be part of a system that also includes an airtight air barrier that keeps household air (with its moisture and heat) out of the rafter bays.

Jeff says

This is what I did in my family room with rafter baffles from the soffits all the way to the roof vents, then I faced baffle insulation, then foil faced 1” foam board. Foil Taped all my seems. Before we ever got to putting up the tongue and groove ceiling we have moisture dripping all over from under the tape. We live in central Minnesota. Thoughts?

buildingadvisor says

Is this new construction or are you retrofitting the insulation to an existing roof structure? If it’s new construction, the moisture source could be the new roof/ceiling joists that are drying out in their first heating season. Moisture problems related to new construction often resolve themselves after the first year.

Otherwise, it sounds like there is a significant air leak into the roof cavities and maybe high moisture levels in the air inside your home. Do you know what the relative humidity is inside the house? Do you use bath and kitchen exhaust fans? Have a wet basement, lots of house plants, or firewood drying inside the home? These are common sources of excess indoor humidity.

As for air leakage, do you have any holes in the foam board for ceiling lights or other plumbing or electrical penetrations? Did you get a positive seal around the perimeter of ceiling.

Finally, the source of the moisture could be windblown snow or rain that entered through the ridge vent. Most ridge vents have either wind baffles or filter materials to block entry of windblown moisture, but these systems are not 100% effective.

I’m also wondering about what type of tape you are using to seal the foam board. The tape used to seal seams in insulation is generically called “contractor’s sheathing/seaming tape” or vapor barrier tape. It’s often red like the 3M Construction Seaming Tape. These tapes have very aggressive adhesive that sticks to just about anything and is highly water-resistant.

If water is leaking down through the tape, then maybe air is leaking up through the seams and carrying moist air into the roof cavity.

Do any of these explanations fit for you?

Jeff says

Thanks for the quick input. It is a retrofit because the previous installation had no air baffles. We had to take down the old ceiling and insulation and cut in air passages from the soffits. The ridge vent does have a mesh type filter. I don’t have a real scientific answer on humidity, but we have a indoor/outdoor sensor in the room and it’s about 38%.

I didn’t know that there was a difference in tapes. We used foil tape that is used on ducting. Maybe I should pull this off and reapply the proper tape? Any recommendations on tape? The foil tape is peeling up all around the perimeter and across seams and this is where the drips are coming out.

The warmer the day, the more moisture. There are 3 modern clip-in recessed lights. Not cans. They are only about 1/2” thick. I’m not sure the best way to seal around these. Now that there is moisture there again, do you recommend pulling down the foam and allowing it to dry before re-sealing, or should I just retape and allow it to dry naturally? It’s not soaking wet by any means, but there is enough that it drips. I’m wondering though, the baffles are only 14 1/2” wide while the rafters are 16” oc, does the insulation touching the roof deck allow for moisture to form? Or is this because the air is leaking through the wrong tape used?

buildingadvisor says

Moisture problems often take some detective work to identify the source. It sounds like your indoor humidity levels are OK, so my guess is that a lot of household air is leaking into the roof cavities. In cold weather, the warm air in your house wants to escape through the roof due to the stack effect. The air will find its way through any small seams and gaps in the ceiling. There is probably frost from condensed moisture on the underside of the roof sheathing that melts on warm days and drips through gaps in the foam.

As mentioned in the original posting, a 2 in. vent space performs much better than a 1-in. space in tests. But the 14½-in. wide baffles should be fine for rafters 16 in. o.c.

Foil-faced tape is a good choice as long as it is UL-listed – that should be printed right on the tape. However if it is peeling, that’s a sign that the adhesive is not providing a good seal. Cleaning the foil facing with a swipe of isopropyl alcohol before applying the tape can help insure a good seal. Also, using a rubber hand roller on the tape can helps make a good bond.

I have mostly used acrylic tapes designed for construction and vapor-barrier joints, such as 3M Construction Seaming tape. But the foil tape designed for ductboard is also a good choice.

As for the recessed lights, sealing them from below is difficult as there are usually a lot of cutouts and holes in the housing unless you purchased special airtight fixtures. With access from above, contractors can build or install airtight covers on IC(insulation contact) -rated units, but this is not an option in a cathedral ceiling.

From below, you can seal around the perimeter of the light housing with canned foam. But it is difficult to seal the rest of the fixture without voiding the light-fixture warranty and possibly creating a fire hazard. Most modern fixtures have built-in overload protection, and modern CLF and LED bulbs create a lot less heat. Still if you want to avoid any risk of overheating, you may be best to use an airtight fixture such as the LED Retrofit Module from Cooper Lighting.

If you can remove the tape and clean off any tape residue with isopropyl alcohol, you may be able to reseal the joints after everything dries out. But that probably means waiting until much warmer weather arrives. Hopefully, you won’t have to remove and reinstall the foam board.

Reid says

Insulating an Unvented Cathedral Ceiling

Our summers in northern California can be pretty hot & I am looking to add more insulation to my attic.

-the attic floor is insulated already

-there is a ridge vent

-there are 2 gable vents, 1 has a fan

-there are 2 between rafter vents

-there are no soffits or eaves, so no vents there

So I wanted add insulation between the roof rafters. I can’t seem to find any information online about my particular design because I have no soffits or soffit vents. If I insulate do I still need to add or make soffit insulation baffles?

Thanks!

buildingadvisor says

First you need to decide whether you want the attic to be conditioned (insulated, heated, and cooled) or unconditioned space.

If I understand you correctly, you have treated the attic as unconditioned space by insulating the attic floor and venting the attic with gable-end, roof, and ridge vents.

If you don’t plan to use the attic for living space, you could add more insulation above the floor. This could be cellulose, unfaced batts, or rigid foam board. You could add a new floor on top of the insulation if you want to use the space for storage or need it for access.

If you want the attic to be conditioned space that is heated and cooled, then your best bet would be an unvented cathedral ceiling — sometimes referred to as a “hot roof”. You could leave the ceiling insulation in place, providing some additional insulation for the living space below.

Experts have debated the pros and cons of hot roofs for decades. I’m not a big fan, but they can work if done carefully and the roof is well-maintained and free of leaks. In a mild and dry climate like California, you should probably be fine If you follow these recommendations:

• Place the insulation between the rafters or below them.

• Use closed-cell spray foam, closed-cell foam board (extruded polystyrene, such as Dow Styrofoam), or foil-faced iso board.

• Seal the insulation or the ceiling surface below against air leakage. You don’t want moist air leaking into the roof cavity.

• Do no use a vapor barrier under the insulation. If required by code, use one of the “smart” vapor retarders such as Membrain.

If you chose spray foam, you can save money by spraying a couple of inches of foam against the underside of the sheathing and filling the rest of the cavity with cellulose or fiberglass. The install drywall and seal it well at the edges to prevent air leakage.

You can read more at these links:

Cathedral Ceilings, Insulating with Spray Foam

Cathedral Ceilings, Unvented, How to Seal

Paul Loughnane says

Hi Steve

I very much appreciate the quick and detailed reply. Yes – it’s completely open from below with the rafters and roof sheathing all exposed (see photo). My goal is simply to make it a reasonably comfortable workshop that I can heat and cool without needing to completely overkill on the HVAC due to zero insulation (although my usage isn’t going to be that high, so I’m not too worried about utility bills).

I didn’t plan on finishing the space so do like the sound of the iso-board solution – in that case can I go without venting or would that cause a problem if I wanted to finish it with drywall on top at a later date?

When you talk about venting, there are no vents to the outside currently, so are you talking about internal vents top and bottom to allow interior air to circulate? Would this need to be provided between all rafters?

My initial research led me down the path of closed cell foam but I didn’t realize how expensive it was (also needed to add intumescent coating if leaving it unfinished).

The second photo is of the adjacent garage space that’s part of the same building. While I’m only considering the workshop space for now, depending how that works out, I may do something similar in there at a later date.

Thanks,

Paul

buildingadvisor says

Hi Paul,

Thanks for the pics. Because of the roof framing layout, you would have a difficult time venting from the lower to upper edge of the roof. You would need to leave a 1-1/2 to 2-in. vent space under the sheathing and drill holes or cut notches in the cross pieces for continuous venting. And you would probably end up with minimal ventilation for your efforts.

Some people nail flat 2x4s on top of their existing roof and build a new roof to create a vent space, but it would be hard to justify the cost for a workshop.

So an unvented roof is probably your best option. As for iso-board vs. spray foam, the iso-board would be a lot cheaper – especially if this is a DIY project. To simplify things, and save a lot of time cutting and fitting, you could just nail the iso-board to the bottom of the rafters. Seal the seams with contractor’s tape and seal the foam board edges to the wall with spray foam.

If everything is well-sealed and the workshop space is pretty dry in the winter (no hot tub or drying firewood), then I wouldn’t worry too much about roof problems caused by interior moisture. I’d be more concerned about roof leaks – make sure you don’t have any currently – and maintain the roof well. When it’s time to reroof, cover the whole thing with peel-and-stick membrane as an underlayment or consider a singly-ply membrane such as EPDM, which can last 30 to 50 years.

To be extra careful, you might consider adding vents at the top and bottom of the roof – soffit vents at the bottom and a soffit vent or shed-roof vent at the top, depending on the detail. Then drill a few one-inch holes in the cross pieces along the middle of each 2x, but not too close to the ends. See our Notching and Boring Guide for where to drill or notch.

With closed-cell spray foam, in theory, you get some drying toward the interior – but not much. With foil-faced insulation, you get none, so the ventilation space is a good idea. Most likely you will never have a problem, but better safe than sorry. The air space above the insulation will provide some relief in the event of a roof leak, even without ventilation. It’s better than having the water sandwiched between the sheathing and spray foam.

As for how much insulation to use, the minimum would be a 2-inch board, which will get you about R-12, plus a little extra from the foil facing. R-12 may not sound like much, but you’ll have continuous insulation with no thermal bridging through the rafters. Compared to what you have now – about R-2 maybe – you’ll be reducing heat loss through the roof by about 80%. If you double the insulation from R-12 to R-24, you will only reduce your heat loss by another 10% for a 90% reduction. That’s how the numbers work for insulation – the biggest bang comes with the first increase in R-value – the so-called Law of Diminishing Returns.

You can always add a finished ceiling later, either nailing/screwing through the foam or adding a layer of strapping first for easier nailing and another insulting air-space. With a shiny foil surface and a ¾-inch air space, you get a boost of about R-2 for heat flow upward (winter) and double that for heat flow downward in summer.

That’s what I’d do if it was my shop. Being in northern Vermont, I might price out 3-in foam if you can get it, or figure out a way to install R-15 3-1/2-inch fiberglass batts above the foam (you’d have to add some 2×4 joists between the structural one) but the additional savings would be modest.

Paul Loughnane says

I think the iso-board attached directly to the bottom of the rafters is the way to go for all the reasons you’ve outlined (simplicity, cost). I’ll look around to see what thicknesses are available but 2″ seems to be the standard in-stock item at the big-box stores. Lowes has a 2″ Johns Manville product that is R13.

Do I need any kind of vapor barrier or such between the board and the rafters – I don’t see why I would if the board is impervious to moisture but wanted to ask as I saw pictures of this being applied in some of my internet searches!

I understand the need to seal to the interior well, but what about the air pockets between the board and exterior – there may be some minor air leakage to the exterior down around where the rafters meet the tops of the walls – should I seal all that up so the air pockets are totally sealed or does it matter?

And final question (I think) – am I right in thinking that the roof is by far the bigger source of heat gain and loss, but if I wanted, could I use the same method on both the wood stud and cinder block exterior walls , simply attaching the insulation directly on top and sealing as before?

I can tackle most projects and am very careful and thorough when I know what to do, but am simply lacking the know-how/experience in this case so do very much appreciate your time and advice.

Thanks, Paul

buildingadvisor says

In answer to your questions:

1) No, you do not need an additional vapor barrier with foil-faced insulation. The foil facing is impervious to moisture and air as long as you seal the joints (with tape) and seal the edges (with spray foam).

2) Regarding air leakage from the block cores into the ceiling: Unless you are on a very wet site or you have wet snow piled against the unfinished block on the exterior, I wouldn’t be too concerned. Energy experts love to say things like “Make sure the ceiling is 100% airtight.” But in the real world, this is easier said than done. If you can block the tops cores of the block wall with spray foam, that would be good. It’s hard to give a definitive answer. If concerned, you can get a humidity gauge to make sure the indoor RH is below 40% in winter. If necessary (unlikely) you can run a dehumidifier as needed.

3) Regarding roof insulation vs. wall or floor: It is a common misunderstanding that roof insulation is more important than wall insulation because “heat rises.” Hot air does rise, but the temperature at your ceiling is, at most, a couple of degrees warmer than at the floor or walls. So the heat loss from conduction is about the same. Square foot for square foot, walls, ceilings, and floors lose heat at about the same rate. The reason that codes require a lot more insulation in ceilings is because attic insulation is generally cheaper than wall or floor insulation (because you can just blow in gobs of the stuff in an attic). So the cost-effectiveness equation points to more attic insulation than walls. In your case, adding insulation to your open stud cavities would be very cost effective.

In the summer, roof insulation is more important than walls and floor insulation for summertime comfort and air-conditioning costs. If that’s the case, a radiant barrier (or white, reflective roofing) is usually more cost effective than adding lots of high-cost foam insulation.

The economics of insulating cathedral ceilings is more like walls (expensive to insulate) than attics (cheap to insulate). But codes rarely make the distinction between attics and cathedral ceilings in the minimum insulation requirements. So some people go to crazy lengths trying to reach R-40 or R-50 in their cathedral ceiling while their money would have been better spent on better air sealing, better windows, more efficient heating system, or increased wall insulation. It’s a matter of optimizing your dollars spent on energy efficiency to get the best bang for the buck. Putting all your money into ceiling insulation while ignoring the walls, windows, and air-sealing is not going to produce the greatest possible savings.

Energy and moisture advice can be very confusing and sometimes contradictory. Also, there are site-specific issues (like moisture) so that what works in one building can lead to disaster in another – especially if there is an unusual source of moisture. So it’s definitely worth sorting out all the issues ahead of time. Best of luck with your project!