Don asks: Our house measures just over the EPA limit for radon. Is this something we should be concerned about or are the risks overblown? How effective are radon mitigation systems and what do they cost? — Doug M.

Steve Bliss, of BuildingAdvisor.com, responds: While radon stories rarely appear in the news anymore, the health risk from exposure to high levels is real and significant. Public health experts agree that radon is a leading cause of cancer in the U.S. It is the second leading cause of lung cancer and is responsible for approximately 20,000 deaths each year in the U.S., 3,000 more than are killed in drunk-driving accidents. Smokers are at the greatest risk, roughly ten times greater than non-smokers – because smoking and radon have a combined “synergistic” effect.

To put the risk in perspective, the lifetime cancer risk from living in a home with a radon level of 4 pCi/L (the EPA “action level”) is about 6 in 1000 – about the same risk you have of dying in a car crash. For smokers, the risk is 6 in 100, a pretty scary number. By comparison we don’t allow any substance in drinking water that poses a cancer risk greater than 1 in 100,000. The radiation level at 4pCi/L is 35 times higher than we accept for people living near nuclear waste sites. Because radon is invisible, odorless, and difficult to regulate since it occurs naturally, we tend to ignore it.

The EPA recommends corrective measures when indoor radon levels exceed of 4 pCi/L of air. This “action level” has become the threshold level for many real estate deals. The goal of mitigation work is to get the level below 2 pCi/L, closer to the national average of about 1.3 for indoor levels (vs. 0.4 for outdoors). There is nothing magical about the action level of 4. A level of 3 carries ¾ the risk of a level of 4 and so on. The World Health Organization recommends an action level of 2.7 pCi/L.

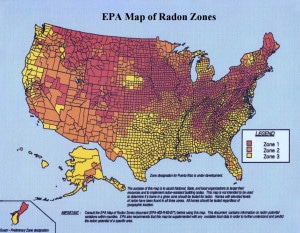

Radon is found in all 50 states, but those in EPA Zone 1 have the highest risk. Some neighborhoods have higher average levels than others, but two houses next door to each other can vary by a factor of 100.

Testing is easy and inexpensive and the only way to determine if you have a problem. Short-term tests of a week or less are good for screening purposes, but long-term tests are more accurate. The test should be done in the lowest level of house usable as living space.

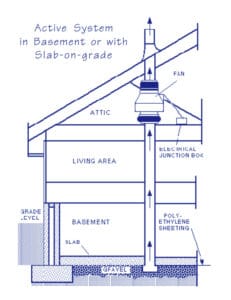

Controlling radon levels is fairly easy in most homes. Typically, a high-quality inline fan is used to draw the gas out from below the crawlspace, slab, or basement, where radon enters a house though cracks and construction joints. PVC drain pipe directs the radon gas to the outdoors. Sometimes a sump, existing foundation drain, or hollow-core block wall can be used as a collection point, but often a hole gets drilled through the concrete slab (see photo).

The fan can go in an unoccupied attic or outdoors. You don’t want it in a location where it will send radon gas into your house in the event of a leak or break in the piping. A good quality installation is extremely quiet and the fan should last 10 years or more. I recently installed a system with the fan in an attic space adjacent to the master bedroom (see photos above). The fan noise is not detectable. Despite a long duct run with several elbows, basement radon levels have dropped from about 6pCi/L to under 0.4pCi/L, which is the average outdoor level.

Homes with course gravel or crushed stone below the slab are easier to fix than home with a dirt crawl space or a slab directly on dense soil (illustration below). If you hear a hollow sound when you tap on your basement floor, that’s a good indicator that you have a nice layer of stone beneath. With dense, impermeable soil under the slab, you will need a more powerful fan and may need multiple suction points through the slab, which can be determined with simple diagnostic testing. However, nearly all homes can be fixed by an experienced radon contractor. Typical costs range from $1,000 to $2,000 for a professional installation.

The EPA has excellent guides on radon risks, testing, treatment, and construction techniques. including what to look for in a radon mitigation contractor. Also, most states have a radon office or specialist as part of their state health department that can provide expert advice and often offer free testing services. — Steve Bliss, BuildingAdvisor

Download EPA’s Citizen’s Guide to Radon Home Buyer’s & Sellers Guide to Radon

Consumer’s Guide to Radon Reduction Building Radon Out (technical guide for new construction)

Read more on Radon and Building Sites

Fran S. says

Best Building Technique for High Radon Site?

Hello our current home in New England is from the 1800s and even with a radon mitigation system the radon numbers are higher than we would like. Because our foundation is old, has a lot of leaks and with much of it built on or adjacent to ‘ledge’ and clay the radon company says they can’t mitigate any more. We love our site (which is quite small) 1/4 acre but my question for you is if we decide to design and build a new house, with a new footprint and new foundation will part of our radon solution be 1) remove the ledge and boulders that are right next to our house (on the first floor) and 2) re-dig our foundation so we can put in ample gravel below and around the newly poured foundation to get the proper air flow we need? Also, my key question is: do you have any information (links) that shows (that part of a radon mitigation strategy in a new home construction) would be to remove above and below ground boulders/ledge from adjacent to the house/foundation?

buildingadvisor says

As you have discovered, reducing radon with an old foundation and dense, non-permeable soil can be challenging. It also sounds like you may have exposed ledge or fieldstone in your basement, which may be contributing to your radon levels.

I cannot say whether your radon mitigation company has done everything possible to reduce radon levels, but there is a diminishing return for additional efforts. Sub-slab depressurization is almost always the most effective strategy (assuming you have a slab floor), but can be combined with other strategies for further reductions. For example, extensive sealing between the basement and living spaces can achieve further reductions. Adding a HRV to the living quarters could further reduce radon level. But there are increasing costs and no guarantee that you will achieve your target level.

There are technical guides addressing the issue of low-permeable soils, but not all radon contractors are familiar with the full range of approaches.

It is certainly much easier to control radon in new construction. Sub-slab depressurization is highly effective with a 4-in. gravel bed and heavy-duty vapor barrier under the basement slab or slab-on-grade. In nearly every case, sub-slab depressurization in modern homes is able to achieve radon levels below the EPA action level of 4 pCi/L.

Blasting enough to build a conventional foundation with a sub-slab gravel bed below the slab will certainly help you achieve your goal. Installation of one or more pvc stubs through the slab is easily done when placing the concrete. With high radon levels, a 4-in pipe is preferable as it is quieter with higher airflow levels.

If you have interior drainage pipe under the slab, the radon stub can “tee” off from the perforated pipe. This will draw from a much larger area than a single stub into the gravel bed and may be worth the extra expense in your case. Also make sure the contractor uses a heavy-duty vapor barrier under the slab, lapped at least 12 inches at seams, and fitted tightly around any penetrations. Either use a 10-mil barrier or reinforced poly for best protection and durability during construction.

Find a contractor familiar with radon-resistant construction and get your radon-mitigation contractor involved in the planning and supervision of this phase of the project. These details are vastly easier and cheaper to do during construction than later.

Download EPA’s comprehensive guide to Building Radon-Resistant Homes.

Richard says

Should We Test For Radon in Finished Basement?

We have a two-sided basement with one side unfinished and the other finished for a game room. There are no bathrooms or kitchens in the basement. It is not a “livable” area. Should not the test be performed on the next level up…the actual living area…?

buildingadvisor says

In its Citizen’s Guide to Radon, the EPA recommends that radon testing be done “in the lowest lived-in level of the home (for example, the basement if it is frequently used, otherwise the first floor).”

In other documents the EPA recommends that testing devices are “placed in the lowest level of the home suitable for occupancy. This means testing in the lowest level (such as a basement), which a buyer could use for living space without renovations. The test should be conducted in a room to be used regularly (such as a family room, living room, playroom, den, or bedroom); do not test in a kitchen, bathroom, laundry room or hallway.”

It’s a judgement call as to what “frequently used” means. However a finished basement would qualify as frequently used by just about anyone involved in public health or radon mitigation, including state agencies. In general, these folks want testing to done in the lowest level that might be used as living space.

In calculating the health risks of radon exposure, scientists assume that a person spends 18 hours per day at home for 70 years. So if you only spend a few hours per week in your basement, your health risk from exposure there would be reduced significantly. If you are running on a treadmill there, however, and breathing deeply, your exposure would go up. Smokers are also at greatly increased risk. There are a lot of variables.

To be on the safe side and not have to think about it, I’d recommend testing in your basement game room. If you want to play the odds, then test in an open area on the first floor.