Q: I am renovating and old home with an uninsulated, non-vented walk up attic built in 1848. The shingle roof is less than 10 years old. The simple gable roof has 2×6 rafters. I’d like to apply 2 in. of closed-cell foam and then install 3 ½ in. of R-15 rockwool and add an Intello “smart” vapor retarder. The finished ceiling will be1/2” nickel gap shiplap.

Will this approach prevent condensation on the underside of the spray foam? I’m also considering using strips of foam board with taped joints and foamed edges – as an alternative to spray foam. I live in Westchester, NY in Climate Zone 5. — Andy

A: Combining spray foam with fiber insulation in an unvented cathedral ceiling (or wall) is often referred to as “flash and batt.” This is a pretty easy way to boost your R-value and get an airtight air barrier without a lot of fussy detailing or extra-deep framing. It provides many of the benefits of closed-cell foam (higher R-value, tight air barrier) without the cost of filling the whole cavity with foam.

The approach also has the downsides of spray foam – high cost and fact that most spray foams use a blowing agent that contributes to global warming. Some of the newer foams use less harmful blowing agents. Open-cell foam is more eco-friendly, but not recommended for this application because of its permeability to moisture.

Dew Points & Condensation

With flash-and-batt insulation, you need to use enough foam to reduce the potential for condensation on the bottom surface of the foam. This is the first cold condensing surface where water vapor in household air may condense into liquid water. The goal is to keep the interior surface of the foam above the dew point of the interior air for most of the winter. So even if indoor air leaks into the roof cavity, no significant condensation will form.

The colder the climate, the more foam you will need. It works like this: if 50% of the total R-value is in the foam and 50% is in the rockwool, then the temperature on the interior face of the foam will be 50% of the temperature difference between inside and outside. So if it’s 0° F outside and 70° F inside, the temperature of the foam surface will be 35 degrees F.

If 40% of the total R-value is foam, then the temperature on the interior surface of the foam will be 28° F (40% X 70).

Code Requirements

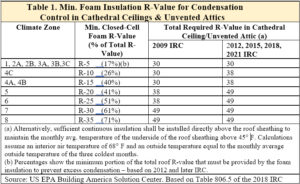

The IRC building code requires that the average monthly temperature on the interior face of the foam during the three coldest months be above 45° F (about 7° C) . In Climate Zone 5, that works out to R-20 foam with a total R-value of R-49, based on the 2021 IRC. The key issue is the ratio of foam to fibrous insulation. In this climate zone, the foam should account for at least 41% of the total R-value (see Table 1 below).

In your case, you have a total roof R-value of about R-25 and a foam R-value of R-12 to R-13 (for 2 in. of closed-cell foam). That puts your foam R-value well above the recommended 41% ratio for DOE Climate Zone 5.

This assumes an aged R-Value of R-6 to R- 6.5 per inch for closed-cell foam, a fairly conservative number. The measured R-value of spray foam after 6 months ranges from just under R-6 to just over R-7 depending on a host of variables, including the thickness of the foam (thicker is better), the material sprayed to (metal is better than wood or concrete), the formulation and application of the foam, and the test method. Tests conducted by the US Navy and others on closed-cell spray foam after 5-10 years show R-values ranging from R-5.8 to R-6.2 per inch for 1-3 inches of foam applied to a wood substrate (read more on test results).

Since you have no control over most of these variables, it’s best to assume a long-term R-value of about R-6 per inch.

Air Barriers and Vapor Retarders

There is no real consensus on the need for an air barrier and vapor retarder below the insulation.

Some contractors and energy experts say that you don’t need an interior air barrier or vapor retarder because the foam provides an excellent air barrier and is warm enough that you don’t need to worry about condensation.

With properly applied spray foam, and the right ratio of foam to fluff, this may be true. If you use “cut-and-cobble” foam board, however, it is harder to achieve a perfect air barrier. Also the wood rafters act as thermal bridges, and will tend to be colder than the interior foam surface.

In addition, workmanship on most job sites is less than perfect (and wood and buildings move over time). So I always prefer a belt-and-suspenders approach. For those reasons, I still recommend a tight interior air barrier and a moderately permeable Class III vapor retarder (1-10 perms) with flash-and batt-systems. Ordinary latex or enamel paint on drywall works fine as the vapor retarder.

A smart vapor retarder like Membrain or Intello is also a good choice as it can provide a good air barrier, if installed carefully, in addition to a vapor retarder that becomes highly permeable when wet. This is an ideal product for this approach and would be a good solution with your shiplap ceiling.

It’s important to retain some drying potential to the interior in case the cathedral ceiling cavity gets wet despite your best efforts. The source of the moisture may be a roof leak rather than condensation from indoor air.

So a low-permeable vapor barrier like poly sheeting should never be used below foam insulation, whether it is foam alone or foam plus fiber. Any moisture that gets trapped between two impermeable materials will linger, leading to mold growth, wood decay, and possible insect damage.

Cut & Cobble

You also mentioned that you might cut strips of foam board to fit between the rafters as an alternative to spray foam. This is definitely cheaper if you provide free labor. However, this approach, sometimes called “cut and cobble” is very labor intensive and getting the required air seal takes effort.

You will want to tape all foam-to-foam joints with a high-quality construction tape that is suitable for the type of foam used. Also, you’ll need to foam the outside edges where the foam board meets the wood framing. Standard home-center canned foam is not up the task. A larger professional-style foam applicator is needed for the job. And wear gloves, mask, and throwaway clothing as spray foam is nasty stuff and impossible to remove from clothing.

So, yes, it’s doable, but definitely get a price from a spray foam contractor and you might think twice about doing this yourself. — Steve Bliss, Editor, BuildingAdvisor.com

Read more on:

Foam Insulation Thickness on Walls.

Insulating Cathedral Ceilings with Spray Foam

Insulating with Foam Board

Preventing Condensation in Cathedral Ceilings

Sealing Unvented Cathedral Ceilings

Josh says

Can I Use Two Inches Foamboard as Insulation and Vent Baffles?

I’ve searched your site and found several very helpful articles and follow up discussions regarding insulated cathedral ceilings, so thank you! However, I’m unfortunately halfway into a DYI project and now want to make sure I complete it the correct way.

I live in MO – climate zone 4A. I’m reclaiming some attic space for a bedroom expansion and the attic space has an A-frame ceiling (12/12 pitch) Rafters are only 2×6. Based on other (maybe wrong) advice I found before this site, I’ve furred out the rafters to allow 2″ of foil faced poly-iso foam board (foil faced in) with 1″ vent space against roof sheathing. I was going to seal this with spray foam/tape really well, install my batts (faced, against interior finished surface) to achieve my R-38 value, and then finish with tongue-groove wood. Walls, including knee walls against the cathedral ceiling, will be R-13 batts to match existing walls.

It’s a complex roof but I have soffit vents where the soffit exists. No ridge vent (I intend to install one next roof replacement on all ridges, which is probably in next 5 years or so), but the main attic has the old style spinning exhaust vents. I’ll have airspace with the vent system I created with the rigid board to connect to these areas.

After reading your articles, I now realize the best approach would have probably been to install the board OVER the rafters, and had batts within the rafters spaces, and losing a little more headspace.

I THINK I have enough rigid board in my current plan to prevent condensation issues, but am questioning now if I need to install an additional thin rigid board over the rafters to finish it off and seal, or if that would potentially be worse to trap any moisture between the foil iso board and the interior board? I’m also unsure if I should still seal my iso board, and about my faced vs unfaced batts…. Any suggestions given I’ve installed the rigid foam as “cut cobble” already but haven’t sealed yet would be greatly appreciated!

buildingadvisor says

If I understand you correctly, starting with your roof sheathing and working downward, you have a 1 in. air space, 2 inches of foil-faced isoboard, faced fiberglass batts, and t&g boards for your interior finish.

If you study the table in the article above, you’ll see that the foam insulation should account for at least 40% of the total R-value in the roof assembly to avoid excessive condensation on the bottom surface of the foam.

In your case, the two inches of iso-board only account for 32% of the R-38 total. (I’m using R-6/inch for the iso-board, a realistic estimate.)

Unless you wish to add another ½ inch or more of iso-board, you will have to work extra hard to keep moist air out of the roof cavities. That would require an airtight air barrier on the warm side of the ceiling. This is typically a sealed panel material such as painted drywall – well sealed at joints and perimeter.

Another option is one of the “smart” vapor barriers such as MemBrain, installed in an airtight fashion across the bottom of the rafters. Whatever material you use for youf air barrier should be moderately permeable to moisture (a Class III vapor retarder of 1 to 10 perms). This will allow your roof assembly to dry to the interior as needed.

I would definitely seal the iso-board pieces at joints and perimeter, or you will lose a lot of the R-value provided by the foam. Some builders who use carboard or thin foam baffles, leave the baffles intentionally unsealed so any trapped moisture can find its way into the vent space. This seems logical, but not sure it has been tested.

An, no, I wouldn’t add another layer of foamboard below the rafters for the reasons you cite. Every building assembly needs the ability to dry out in at least one direction.

The vent space above the iso-board, gives you a little extra R-value (due to the foil), and a radiant barrier in summer that will be improved with the ridge vent. If you ever get a roof or flashing leak, and working soffit and ridge vents, you will have a more durable roof that is able to dry out also the the exterior. So it could work well in the end.

Martin Uildriks says

Spray Foam Vs. Flash & Batt vs. Cut & Cobble?

I have an uninsulated roof with 2×6” rafters, which I plan to insulate, but I’m still deciding on the best and most cost-effective solution; time and money are both considerations. I’m in New York Westchester, like the original poster, and the surface area of my roof to be insulated is roughly 2,800sqft. I see a few possibilities to do this, but I would appreciate your input on the issue of condensation since some part of the roof space will, in the future, become part of a cathedral ceiling (currently I have a mostly insulated ceiling that I will break open to convert the living room to cathedral ceiling).

My options are:

– 5.5” of close cell spray foam, total of c. 2,800×5.5” = 15.400 board ft (found someone willing to do it for $12k);

– flash-and-batt: 2” of close cell foam with 3.5” fiberglass batts (est. $5k + $2k for batts);

– cut-and-cobble: 2” Polyiso fixed with close cell foam followed by 3.5” fiberglass batts (est. $3k + $2k for batts);

I’m tempted to pursue option 3 (I do quite a bit of DIY) and I’m now wondering if sealing the rafter cavities with an inch of Polyiso attached across the rafters, with drywall and a few layers of latex on top, would be a good idea as well. Would that keep eliminate any chance of condensation on the sheathing and simultaneously isolate the rafters as a thermal bridge? The reason this is on my mind is because I plan to convert some part of the current attic into a cathedral ceiling with skylights/windows in the roof to let in natural light; I’d remove all ceiling insulation, tear out some ceiling and extend the living room walls to the roofline. I hope to have a long and slightly large window (let’s say double-glazed, 4×8’ though size and position is still to be decided) installed along the length of the living room. Would that impact the whole humidity/condensation/moisture situation at all?

Thanks for a great and very informative article and discussion board!

buildingadvisor says

All you options seem feasible — with all the pros and cons of unvented “hot” roofs. The main drawbacks, from my perspective, are twofold:

– Good performance is very dependent on workmanship for both commercially applied spray foam and cut-and-cobble. A sloppy job risks both thermal and moisture problems.

– The inability for the roof structure to dry out in a reasonable amount of time if there is a roof leak or condensation problem — combined with the inability to detect the leak visually. With closed cell foam or foil-faced foam, drying downward into the home is virtually eliminated. With an impervious roof underlayment of roofing material, drying outward is also not an option.

If you roofing materials are impervious to moisture, then you might want to consider XPS or EPS for Option 3 or 3 plus foamboard under the rafters. I like the layer of foamboard below the rafters to reduce thermal bridging and create a continuous air barrier. However, if you plan to install skylights, you will have to very carefully seal the foam board to the skylight.

The window you describe should not pose any problems as long as you seal and flash it properly. At the top of this wall, and all other walls and partitions that terminate into the cathedral ceiling, make sure there are no unsealed leaks into the cathedral ceiling for pipes, wires, chases, or other building components.

Russell says

Best Way to Spray-Foam an Attic

I am remodeling about half of my house and putting closed cell foam in the ceiling of the remodeled part of the house. The existing (unmodified) part of the house has 12″ of fiberglass in the attic between the ceiling joists. The contractor is recommending I spray 5″ of closed cell foam on the inside of the roof (enclosing the roof rafters). He says that will give me an R value of 50. Using an R value of 6 per inch the foam would only give me an R value of 30 which is the same as (or at least not much better than) the existing fiberglass.

He tells me the calculated R value is actually higher because of the reduction of air leaks but I suspect this is already accounted for in the published R values for foam. Does leaving the fiberglass in the ceiling add insulation value to the 5″ of foam applied to the inside of the roof if the attic is unventilated? And is it advisable to leave the attic unventilated in such a situation?

buildingadvisor says

If I understand you correctly, the contractor is proposing spraying five inches of foam against the undersize of the roof sheathing, while leaving 12 in. of fiberglass on the ceiling below.

Five inches of closed-cell foam does not provide R-50. You are correct that it is closer to R-30. It’s true a well-done foam job will provide a nearly airtight roof structure, which will reduce air leakage and heat loss, but it does not increase the R-value. R-value measures heat loss by conduction through materials, not by air leakage.

Maybe your contractor is suggesting that the tight foam is just as good as R-50 fiberglass with air leakage, but that’s marketing, not science.

As for ventilating the space below the spray foam, that makes no sense at all. It would render the spray foam mostly useless as cold air would bypass the insulation.

If the foam is installed properly, it will create a near-complete air seal at the roofline, and seal any soffit or ridge vents. In that case, the attic is now conditioned space, inside the building envelope. You can leave the floor insulation in place, but it’s generally not recommended. The insulation should either go in the ceiling or the roof – whichever you want to be the thermal envelope – the boundary which separates the conditioned space from unconditioned space.

If you want to combine foam and fiberglass, the two best options are:

1) Ceiling Insulation: Remove the fiberglass, spray the top face of the ceiling drywall, and then replace the fiberglass and add more (or cellulose) to achieve your target R-value. The foam air-seals the attic at the floor level. You can use just 1-2 inches of inches of foam for a good air seal or as much as you like. Then ventilate the attic above the insulation. The attic would be unconditioned.

2) Roof insulation: Spray the underside of the roof with foam. Then install fiberglass (if desired) under the foam. You may need to extend the framing to hold the additional fiberglass. The attic would become an unvented and conditioned space. People use various approaches to increasing the depth of the roof rafters: 2x4s with plywood gussets is one approach. Running 2x4s or 2x6s horizontally across the bottom of the rafters is another. If use foam with fiberglass below, follow the guidelines in the article above to determine the minimum thickness of the foam needed to avoid moisture problems.

Either approach can work well. Unless you wish to have a usable attic, insulating the floor is usually much more cost-effective.

Read more on: Insulating Cathedral Ceilings with Foam Preventing Condensation in Cathedral Ceilings Sealing Unvented Cathedral Ceilings

Jean Charron says

Should Foam and Fiber Ceiling Have Vapor Barrier?

I have a 2×12 hand-cut cathedral ceiling, currently insulated with R-38 fiberglass batts and covered with a 6 mil vapor barrier. Although I only require R-10 closed cell foam for our 4c zone, I’ll be removing the fiberglass insulation to spray-in 3″ of closed-cell foam (R-18). While I already have fiberglass insulation available, I intend to re-install it over the foam.

According to all the information that I’ve read here, it appears that I’m limited to re-installing approximately 5.5″ of the fiberglass insulation (total R-20) to meet the R-38 IRC criteria for a 4c zone. Correct me if my math is wrong. I only have a couple of remaining questions:

1. If my night time interior temperature is normally a little higher than 68F, does the fiberglass insulation need to be thicker or thinner than the prescribed value?

2. Should I re-install the vapor barrier or simply drywall over the exposed fiberglass insulation?

Thanks for your great article and advice.

buildingadvisor says

Your math is correct. With a total insulation level of R-38, your foam layer needs to be a minimum of R-10. You are well above that with R-18.

The IRC calculations assume an interior temperature of 68F, but a couple of degrees either way will not affect the recommendations.

Finally, a poly vapor barrier is not a good idea as this type of ceiling dries primarily to the interior. However a tight air barrier at the ceiling level is always recommended. This can be the drywall itself if all seams are taped and mudded, and edges are air-sealed around the perimeter of the ceiling with high-quality sealant or gasketed to the framing. Also, do not penetrate the ceiling drywall with recessed lights or other holes that cannot be well sealed. Two coats of latex paint will provide an adequate vapor retarder.

While it’s true, in theory, that the underside of the spray foam is warm enough to prevent condensation — with or without an air barrier — I always assume that materials and workmanship may be less than perfect. So keeping excess moisture out of the ceiling cavities is always the prudent approach — in case some areas of the roof sheathing are not fully protected by the foam layer.

Robert F. says

Can Rigid Foam Between The Rafter Work As Baffles?

I’m in Delaware which is zone 4. I am finishing an attic room with cathedral ceilings. I need to allow air flow from the soffits to the ridge vent. My plan is to use 2 in faced closed cell rigid foam cut to fit in between the rafters, with 2 in spacers to hold the insulation away from the roof. This creates the needed air channel. I’ll seal all joints with spray foam. The rigid foam has facing on both sides, the foil side that will face the roof

In doing so, there is a gap of about 3-4 inches from the foam board to the drywall. I plan to fill this gap with unfaced insulation so as not to create a second moisture barrier. Most likely Rockwool as I hate working with fiberglass.

Does the above approach sound ok?

Bob

buildingadvisor says

If you look at Table 1 in the article above, you’ll see that the foam should account for between 26% and 40% of the total R-value, depending on which part of Zone 4 you are building in. You are well within that guideline with R-12 to 13 for the foam and R-12 to 13 for 4 inches of rockwool. So your foam layer is providing about 50% of the R-value.

Whether your total R-value of 24 to 26 meets your local energy code is a separate question.

The goal is to keep the bottom face of the foam above the dew point of the interior air for all but the very coldest days of the winter. This keeps condensation on the bottom of the foam to a bare minimum, even if your ceiling air barrier is less than perfect – although you should still make it as airtight as you can.

The approach you are taking is often used without a vent space, but you have the best of both worlds — virtually no condensation in the roof plus a vent space below the sheathing to permit drying in case the sheathing or framing ever gets wet from a roof leak.

The upward-facing foil will give you a little boost in summer as well due to the radiant barrier effect, although over time it tends to collect dust and its value is reduced.

Spence says

Will Closed-Cell Foam Stop Cathedral Ceiling Condensation?

Thank you for the information on this. I am having some condensation issues with my vaulted roof. It has Tongue and groove pine with no vapor barrier between the rafters and the insulation in the ceiling is only R 30 faced batts. After very cold days I get condensation due to the water vapor condensing on the roof decking, turning to ice and then melting when it warms up.

My thoughts on how to correct this:

My roof structure does not allow for roof venting due to how it was framed.

8 inches of closed Cell Foam spray in the 12 inch rafter space which is an R-value of 48. this closed cell foam will be sprayed directly on the bottom side of the roof decking creating a “hot roof.” I am in Zone 6 for insulation.

On the inside I will install drywall and paint 2 semi gloss coats of paint to help with vapor on the interior. Then I will put my tongue and groove pine ceiling back up.

Will this solve the issue?

Thanks in advance on the advice.

buildingadvisor says

A hot roof design, like you are describing, should perform fine with 8 in. of closed-cell foam. Just make sure you hire an experienced insulation contractor, as it takes some skill to maintain quality control and to avoid gaps or foam that pulls away from the framing as it dries.

You could fill the rest of the rafter space with unfaced batts for the extra R-value and still be well within the limits shown in the table above. The goal is to have the underside of the foam (the “principle condensing surface”) above the dew point of the indoor air on all but the coldest winter days.

I would install the drywall in an airtight manner as an extra precaution – that is high-quality sealants or gaskets around the perimeter of the ceiling and sealant or foam at any other gaps or openings. While the foam is, in theory, airtight and not in need of a second air barrier, I always assume that construction on site will be less perfect than the drawings.

Since this assembly can only dry to the interior, I like to use a Class III vapor retarder (1-10 perms), so even three coats of standard latex paint is OK. Another, more expensive option, is to use a smart vapor retarder like Membrain or Intello – sometimes required by code.

If the t&g pine is finished, that will also provide an additional bit of a vapor retarder. Even though t&g is very leaky stuff, vapor retarders still work with holes and gaps. A vapor retarder that covers 90% of a surface is 90% effective. An air barrier, however, needs to be close to 100% sealed to do its job.

Stephen says

How About Sandwiching Fiberglass Between Two Layers of Foam?

This is a well written article! Thank you!

Have you ever heard of anyone making a foam-and-batt sandwich? E.g., A hot roof with a flash-foam coating under the sheathing, fiberglass batting fill, then closed-cell foam flashed over the batts (under the drywall) to seal the whole kit and kaboodle?

Thoughts?

buildingadvisor says

No, this is not a detail I’ve seen — nor would I recommend it. Hot roofs are designed to dry to the interior and you are preventing this with the bottom layer of foam.

Potential problems:

1) By adding foam below the fiber insulation, you are cooling the foam under the sheathing. If any indoor moisture reaches the underside of the sheathing it may condense. It will be trapped between two layers of foam.

2) In the event of a roofing or flashing leak that wets the roof cavity, you are trapping water between two layers of foam.

I tend to be conservative with building techniques. I prefer to stick with materials and details that have stood the test of time. I’ve seen too many innovative building systems fail badly over the years. However, if you want to live dangerously, and think you can get a perfect air barrier with your bottom layer of foam – and believe your roof is never going to leak – then you could give this a try.

Stephen says

I think your thoughts on the matter are sound. In order to minimize potential condensation issues I decided to pony up and spray the necessary r-value/% in my hot roof. I have already done a flash coating and just need to finish it off with the proper %. I really appreciated the links to the zone/climate figures for cathedral ceilings. I am in zone 8, so it says I should have a min. 71% of rvalue in foam before I hit my batt insulation. Riddle me this…

I have 2×12 rafters I am filling. If I put in another 5” of foam over my existing flash coat I should have a closed-cell rvalue of around 42 (if we are at r7/inch.) The leftover cavity space should then support an r19 or r21 batt. …however…this will lower the effective ratio of my sprayfoam to batt rvalue. By my calculations this brings my relative foam to batt rvalue %’s down to something like 62% foam and 38% batt.

To keep the 71% foam to 29% batt ratio it sounds like I would have to put a minimum of r51 foam in. …Does this sound right to you? If I don’t hit my %..does this mean I still risk more condensations?

I sure don’t want to spray any more than I have to for cost reasons…but I also don’t want to wind up with condensation issues even after such an expensive process. I have thought, too, about spraying to r39/r42 and then cut and cobble for the remainder. I do have a lot of salvaged foam from some 5 ½” sips panels. …but man…what a pain to cobble.

Thoughts?

buildingadvisor says

Turns out you shouldn’t have slept through algebra class after all?

Looks like you are doing the math properly, but assuming R-7 per inch for spray foam is a bit on the optimistic side. Published numbers range from R-5 to R-7 per inch, but most research points to R-6 as a more realistic estimate.

And, yes, if you skimp on the ratio – with less foam than recommended – you risk having more condensation form on the bottom of the foam. If you read the footnotes in the table above, you’ll see that the ratios are based on the average dewpoint of the interior air during the three coldest months of the year – a pretty conservative standard.

With an airtight air barrier at the ceiling level, a moderate (Class III) vapor retarder (2-3 coats of latex paint on drywall), and reasonable indoor humidity levels, the amount of condensation should be minimal, even if you skimp a little on the foam. But given the realities of construction, it’s best to assume that nothing will be built perfectly. So I’d use R-6 per inch for the spray foam in your calculations.

And, yes, cut-and-cobble is a pain. If you go this route, invest in a professional foam applicator – makes a world of difference.

Stepthn says

If you are willing and it is not too much trouble, would you please provide me with a little further counsel regarding our previous discussion..

After spraying apx. 6 inches to my ceiling cavities I am a bit pessimistic with my final depth of insulation. I’m no professional at spraying foam and was limited to using the 600 bft kits, so my spray patterns and consistency per cavity does vary somewhat. Even though I had experience doing it before, It took me 2 kits in to get into my groove. …and wow…does it make a huge difference when you have the kits at a toasty 80 deg. (was difficult doing this in the winter!)

The end result was that, while most cavities are right at my target depth of 6” or more, there are some variances that dip well be low that. These “valleys” are sporadic but cause me to question the final step.

We had discussed the recommended charts of apx. 70% of r-value (minimum needing to be foam) if the remaining is batted. If I assume a conservative average of r-30 for my foam effort, that puts me at apx. R43 total w r13 being my batt target. …however, I’m not one that likes to hover at minimums out here for good reason, so I decided to calculate w r-30 being 80% of my total r. The result is total of 37.5 w 7.5 being the remaining batt estimate.

Now….i don’t know about you, but I have r38 batts to work w, so peeling off a measly 7.5 and trying to put this thin layer of cotton candy up just seems like such a PAIN…and maybe even unnecessary.

What all that rambling was to get to was this: If I just close up the ceiling with my wall that has an r30-r45 average (depending on where you look 😃), and leave the extra 4-5 inches void (using 11 1/4:” 2×12 joists), do I risk getting condensation on the inside of my ceiling ply? More risky without batting or less? I’m currently using plywood for the close-up w 3 layers of a good semi-gloss latex paint. I’m planning to have all my lighting outside of the insulated space, and get everything as airtight as possible.

Thank you for your time,

Stephen in Alaska

buildingadvisor says

If I follow you correctly, you’re asking whether it’s preferable to have a few inches of fiberglass on the interior side of the foam – or no fiberglass. In terms of condensation, no fiberglass is preferable as it results in a higher temperature at the lower surface of the foam. The goal is for the lower surface of the foam (the first condensing surface) to be above the dew point of the interior air. So the warmer the foam surface, the better.

Think of it this way: If you hang an unfaced fiberglass batt across the inside of a window overnight, you’ll have a lot of condensation on the glass in the morning. The insulation will make the glass very cold, below the dewpoint of the household air.

It sounds like your ceiling is painted plywood with three coats of semi-gloss. I’m not sure if you plan to seal the joints in the plywood, but as long as the foam surface is warm enough, you shouldn’t have to worry about condensation in the ceiling cavities.

FWIW, the main reason that building codes require more insulation in ceilings than walls is that it’s cheaper to pile insulation in an attic than it is in walls. It has very little to do with hot air rising. In hot climates (not yours) extra attic insulation also helps with air conditioning due to high temps in the attic. However, the same logic does not apply to cathedral ceilings, which cost about the same as walls to insulate. Bottom line: with cathedral ceilings, ceiling R-value should be comparable to wall R-value for optimal cost effectiveness.

Vickie says

Can I Put Fiberglass 4 ft. Below Foam?

I have metal roofing on 1/2-inch OSB and about 1/2-Inch closed cell insulation on the underside of the OSB. Is it ok to put fiberglass batting 3 or 4 feet below the foam, on top of the sheetrock ceiling?

buildingadvisor says

With a gap that large between the fiberglass and the foam, you’re building is gaining little or no additional insulation value from the foam. This is due to convection currents and probably air leakage in the roof cavity. If the space between the fiberglass and foam is vented, you will definitely gain no insulation value from the foam.

It’s possible that the foam will be a little warmer than the underside of the metal roofing, reducing the likelihood of condensation on the underside of the metal. However, this is best addressed by building an airtight ceiling plane to keep household moisture from leaking into the roof cavity.

Also, take a look at Table 1 in the article above to find the minimum foam thickness for your climate zone. Then put the fiberglass insulation tight against the foam for the best thermal performance.